Broadening Access: The Non-Collegiate Students

In the mid-nineteenth century, would-be reformers of Oxford often looked to the Scottish universities as offering ways of addressing decades of stagnant undergraduate admissions and poorly-attended professorial lectures (the latter having been supplanted by college tuition and a narrow curriculum for the BA degree). Oxford’s relatively small undergraduate population, dominated by those intended for the Church or the inheritance of landed property, and containing as it did a conspicuous number of wealthy idlers, compared unfavourably with the position north of the border, where professors could command large audiences of serious-minded students, intended for professional careers. The latter were drawn from a wider social range than their Oxford counterparts, as the blog by Bob Harris has described, and many lived frugally in lodgings. By contrast with Scotland’s democratic education system, Oxford’s exclusiveness, reformers contended, had disconnected the university from ‘the nation’. It was this divergence that the wide-ranging project, labelled ‘university extension’, sought to repair.

Dismantling the religious barriers to Oxford admission and graduation was only part of the story. Indeed, as Stuart Jones’s blog points out, the purpose of the 1871 Act was to enable freedom of thought among those who taught and governed the university, rather than to widen undergraduate access. It was convenient for the Act’s promoters to enlist the political support of Nonconformist opinion in industrial cities under the banner of religious equality. But it was unlikely that many of those Dissenting men of industry and commerce would be clamouring to expose their sons to an Oxford education. College residence, and an extended classical curriculum would delay, and not assist, their sons’ entry into the business world, and might well inculcate habits unfavourable to success in such an environment. Furthermore, repeal of religious tests meant little if the cost of residence in Oxford was beyond the pockets of previously-excluded groups.

Such considerations led reformers, particularly among broad church Anglicans and secularisers, to attempt another radical breach with Oxford’s past. In 1868 they succeeded in overturning the requirement in Archbishop Laud’s statutes of 1636 (and in practice dating much earlier than that) that undergraduates should be members of a college or hall; and repealed the long-standing restrictions, also embodied in the 1636 statutes, against undergraduates residing in lodgings in town. At a stroke, the cost of Oxford residence could be dramatically cut, by removing the need to pay for the heavy overheads, personal service, inflated charges, and often extravagant sociability which college membership demanded.

Shortly before the first ‘Unattached’ students (‘Scholares non Ascripti’ as they were formally designated) arrived, in Michaelmas 1868, one of the first academic heads of the delegacy created to oversee them, George Kitchin announced the scheme in expansive terms in a letter to The Times. He offered an invitation ‘to the whole of the young ability of England’, whom he estimated as numbering thousands of young men, to come and take advantage of Oxford’s educational resources.

'Omnibus’ is inscribed on the Clarendon Building in this hostile caricature of the Unattached Students, c. 1868. Source: Bodleian Library

In the first year, forty-three men did so, of whom one-third were said to be Nonconformists. Numbers peaked around the end of the 1870s, with over one hundred men matriculating as Unattached students per year. The non-Anglican element, though, had not appreciably increased; a considerable majority were found to be members of the Church of England. Nor, indeed, were the sons of ‘day labourers’, or mill-hands, whom Kitchin had envisaged coming to Oxford, identifiable among them. Of the first 500 Unattached students, only four were recorded as sons of ‘artisans’.

Instead, the early Unattached students mainly came from less well-off clergy, professional, and business families. They took lodgings in the least expensive parts of town, such as Jericho and Kingston Road, or between the Iffley and Cowley Roads. While Cecil Rhodes of Oriel completed the residence for his degree, in 1881, in the grandeur of King Edward Street, the future bishop, Hensley Henson, whose father was a bankrupt small businessman, lodged as an Unattached student in London Place, St Clements. There, as Matthew Grimley writes in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Henson ‘eked out a lonely and precarious existence’, reinforcing his lifelong sense of being an outsider. Henson went on to get a first in Modern History as an Unattached student. More often, those likely to do well in Schools migrated in mid-course to colleges, whose financial muscle and prestige continually drained the Unattached of numbers and talent.

A new and unforeseen function for the Unattached emerged when, in July 1873, it was reported of the students joining in the preceding term: ‘one of these was a Japanese, another an African from Sierra Leone’. The latter was Christian Cole, now commemorated as the first Black African known to have studied at Oxford. He was an Anglican, and therefore might have studied at Oxford irrespective of tests repeal; he also had a good grounding in classics in institutions founded by missionaries in Freetown, so compulsory Greek was not a barrier either. Money, however, was. He relied on limited family support which would have insufficient for college residence. The Unattached route enabled him to come to Oxford.

Cole’s entire undergraduate career, from matriculation in April 1873 to graduation in December 1876, and including honours in Classical Mods and Greats, took place as an Unattached student, under the aegis of the delegacy whose office was in the Clarendon Building, in the central University area. He was truly a student of the University. When the support from his relatives began to dry up, and as runner-up in a competitive examination narrowly missed being awarded an exhibition, the delegates appointed him librarian, with a small stipend, overseeing the collection of books accumulated for the Unattached Students in the Clarendon Building.

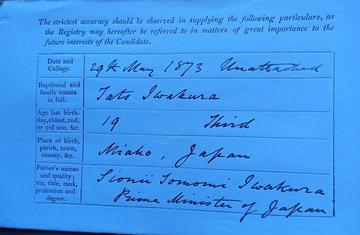

The matriculation form for the first Japanese student at Oxford, 1873. Source: Oxford University Archives.

The Japanese student was the third son of the leading Meiji official Tomomi Iwakura, who led a mission to Europe and the United States between 1871 and 1873. His son’s brief period of residence was a precursor to what become a significant function of the Unattached scheme, in enabling what were called ‘special students’ to come to Oxford to study outside the narrow limits of the BA course. Most were graduates of other universities, and many came from overseas to undertake specialized study. By 1910 over 40 per cent of Non-Collegiates (as the Unattached were renamed in 1884) were overseas students.

At the same time, Non-Collegiates also created, on a small scale, an Oxford equivalent to the localism of English civic universities, where students lived at home while pursuing their studies. Sons of Oxford tradesmen and skilled craftsmen qualified for degrees by this route, some of them having come via the City of Oxford High School for day boys, in George Street (currently the History faculty building), then a significant feeder school to the University and supported by many civic-minded dons.

The building for the Delegacy for Non-Collegiate Students.

As well as a change of name, the Non-Collegiates were given a permanent building in the High Street (now the Ruskin School of Art), next to the Examination Schools. Built between 1886 and 1888, it was designed by T. G. Jackson in – as William Whyte points out – ‘a self-consciously “modern” style’, as befitted a progressive project.

Admitting students living in lodgings, and unconnected to a college or hall, contributed significantly to the diversification of Oxford in the generation after tests repeal. Yet the experiment had not been transformative in the way that its most optimistic advocates had hoped. Indeed, the Bishop of Birmingham, Charles Gore (who had come up to BalIiol in 1871, exactly when the tests were repealed), told the House of Lords in July 1907 that Oxford (and Cambridge) remained ‘a playground for the sons of the wealthier classes’.

Oxford’s reforming Chancellor, Lord Curzon, responded with his famous ‘red book’, published in 1909 as Principles and Methods of University Reform. He reflected on the genuine opportunities that the Non-Collegiate scheme offered, but saw it as an opportunity missed. The University, Curzon suggested, might have done more to advertise the scheme’s benefits, and more funding should have been provided in the way of exhibitions (bursaries awarded on grounds of merit) to assist Non-Collegiates in financing their studies.

Lord Curzon, Chancellor of the University.

Curzon also considered it unfortunate that the scheme had been saddled with titles conveying negativity (as well as otherness), which students were reluctant to embrace. Hensley Henson, like many other former Non-Collegiates who attained conspicuous success in later life, concealed his previous membership of that body in his Who’s Who entry. Meanwhile, the scheme itself acquired collegiate trappings, with its renaming as St Catherine’s Society in 1931. This in turn became St Catherine’s College, which opened in 1962. In the twenty-first century, when Christian Cole came to be commemorated in Oxford, it was in the context of the college of which he was given membership a year after completing his degree, rather than the university scheme which had enabled him to graduate. Thus marked the endings, and in some respects erasures, of a radical project to create an alternative to the college system, in which some Victorians had invested such high hopes as a means of Opening Oxford.

Mark Curthoys, Research Editor, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.