The Abolition of Religious Tests: Some Historical Context

The Universities Tests Act was a landmark piece of legislation in the history of Oxford and Cambridge, and it is well worth using the occasion of its 150th anniversary to reflect on its significance and its legacy. This piece will place it in the context of the national and university politics of its time. If the long-term consequence of the Act, with earlier reforms in the 1850s, was to enable Oxford to become a global university recruiting students and staff globally, it has to be added that nobody envisaged this at the time.

What did the Act do and what did it not do?

The 1871 Act made no formal difference to the right of any potential student to study at Oxford. Tests for matriculation and graduation as BA had been removed by the Oxford University Act of 1854. Tests for the MA and the higher doctorates (DD, DCL, DM) remained after 1854 because the MA, then and now, was a status rather than a qualification, and along with the doctorates was the gateway to the University’s governing structures, as well as to the parliamentary franchise. The 1871 Act was thus not about access to educational opportunities but was about access to power and status within the University. Cambridge had come to a different solution in the 1850s, allowing nonconformists to take the MA (and so to vote in parliamentary elections) but not to be members of Senate. This ‘Cambridge Compromise’ highlighted what defenders of religious tests most valued: the Anglican hold on decision-making. Between the mid-1850s and 1871 Oxford and Cambridge were Anglican universities open to non-Anglican students. What the 1871 Act did was to start the process of dismantling the formally Anglican nature of the institutions. It left tests in place only for degrees in Divinity, i.e. the BD and the DD, which were in any case only open to priests of the Church of England, and would continue to be so restricted well into the twentieth century.

The tests were of two kinds. First, there was the obligation imposed by the Act of Uniformity of 1662: this required college heads and fellows, as well as ‘every Publique Professor and Reader in either of the Universities’, at their admission to office, to make a declaration before the Vice-Chancellor that, among other things, included a declaration ‘that I will conforme to the Liturgy of the Church of England as it is now by Law established’. Second, anyone wishing to graduate Master of Arts, or DD or DCL or DM, or BD, must subscribe to the Thirty-Nine Articles. Of these tests, the first, though well known to be a legal requirement, had fallen into disuse: perhaps rightly so, since it was based on the premise that these office-holders were in Holy Orders, whereas by 1871 only around a half of them were. A junior fellow of Queen’s wrote in 1869 that the declaration ‘is seldom or never regularly or irregularly made’ in Oxford. The second test was certainly enforced, however, and that had implications for college fellows, since at most colleges (Balliol being the exception) fellows were required to proceed to the MA, or to one of the other higher degrees, within a specified period of years. The time allowed was often quite generous, however, so that it was possible for a non-Anglican to hold a fellowship for seven or eight years before resigning. Hence, as the same fellow of Queen’s noted, ‘there are Fellows of colleges of some standing who have neither declared themselves Conformists, nor signed the Articles, nor made any profession of faith whatever at any time.’

University Liberals and the Politics of Tests

How did abolition come about? It’s worth pausing over the fact that this was a parliamentary intervention. Only an act of parliament could release college fellows and others from their obligations under the Act of Uniformity. That was convenient for the reformers. Convocation, Oxford’s governing body, was dominated by country clergy, and that meant that the liberals lost most set-piece battles with academic conservatives, as when the renowned philologist Max Müller was defeated in the election (open to all MAs) for the professorship of Sanskrit in 1860. The High Church party in Oxford was well organized and becoming more, not less, effective in the 1860s. It was, in fact, a deliberate choice by the university liberals to choose to fight their battles in parliament rather than in Convocation.

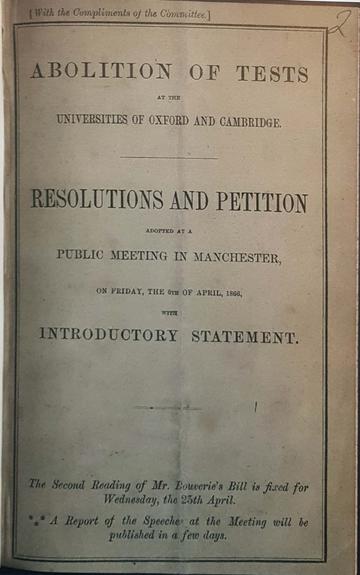

Title page of the pamphlet on the Tests meeting at the Free Trade Hall, 1866.

Agitation for the abolition of tests had been growing in pace since 1863, and the pressure came in the first place not from religious dissenters but from the University Liberals – typically young college fellows, many of them based in London and making a career at the bar or in the higher journalism. By definition, they were (with isolated anomalies) Anglicans by upbringing. They were able to make common cause with the provincial nonconformists, who were powerful and ready to be mobilized behind the cause of religious equality. Together they held a public meeting at the Free Trade Hall in Manchester in 1866 to raise awareness of the issue. Still, many nonconformist activists lacked the same enthusiasm for fighting this cause as opposed to battles over subsidizing church schools on the rates. English nonconformists showed little interest in the right to compete for Oxford fellowships. The centrality of Latin and Greek to the Oxford curriculum meant that nonconformist undergraduates were far fewer than at Cambridge. As Manchester MP Jacob Bright put it, ‘it does not appear that Nonconformists are endeavouring to find their way into the universities so much as that members of the universities are trying to take hold of England’.

Henry Sidgwick was an English utilitarian philosopher and economist. He was the Knightbridge Professor of Moral Philosophy at the University of Cambridge from 1883 until his death 1900.

The initiative lay with the University Liberals. They were certainly committed to reducing the gulf that separated University and nation, but they attached even more importance to questions of freedom of thought and intellectual integrity. They were less concerned by the exclusion of nonconformists than by the dilemmas that confronted college fellows afflicted by religious doubt and a tender conscience. Some had felt obliged to resign their fellowships: a notable example was the Cambridge philosopher Henry Sidgwick, who resigned his fellowship in 1869 (but was appointed lecturer instead) and wrote penetratingly on ‘The ethics of subscription and conformity’. For Sidgwick, the issue was about freedom of inquiry or, still more, about intellectual integrity: nobody, in fact, was stopping him thinking or publishing freely, but he was afflicted by conscientious doubts about holding an office that implied beliefs he no longer held. In Oxford, the same issues triggered the resignation of the freethinking Lyulph Stanley from his fellowship in the same year, even though his college, Balliol, was the only one that did not require its fellows to proceed to the MA.

Non-Sectarian Education or Religious Pluralism?

Bills for the abolition of tests had been tabled in the Commons repeatedly since 1863. What facilitated the passage of the 1871 Act was the backing it eventually received from Gladstone’s Liberal government. That was by no means a foregone conclusion. The relation between education and religion was at the heart of the work of Gladstone’s government, but was also an issue that divided his party, and the ministry never recovered from the defeat of its Irish University Bill in 1873. The Prime Minister himself, a key figure in the reform of Oxford in the 1850s, was a long-standing sceptic about the abolition of tests. A famously devout churchman of Tractarian sympathies, he was committed, like most of the High Church party, to the view that Christian education must be at the heart of a university education. He also held that any Christian education, to be worthwhile, must be grounded in doctrine: non-denominational religious teaching that reduced Christianity to a lowest common denominator was worse than nothing. Two things persuaded him to back the abolition of tests in 1871. One was that if he made the measure a government bill he could ensure that it did not touch the clerical fellowships, which he thought offered a sufficient guarantee of the Anglican character of teaching in the existing colleges. The other was the prospect the Act offered of the creation of nonconformist halls – and potentially colleges – alongside the Anglican colleges: they would ensure the continuation of an authentic Christian ethos in the University, in accordance with the principle that teaching should be ‘free and various’. This was a pluralistic vision of religion in a modern university, and to a degree it was realised in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries with the migration of Manchester College and Mansfield College to Oxford, and the creation of the Roman Catholic halls. But Gladstone’s pluralistic ideal was very different from the vision of mixed, non-sectarian education favoured by most of the university liberals, who wanted to see a bar on the creation of new denominational colleges.

Mansfield College Chapel.

It's when we understand the importance of the tension between the rival visions of mixed, non-sectarian education on the one hand and the pluralistic ideal on the other that we can see that the 1871 Act left much undecided about what place religion would occupy in reformed Oxford. That is why the story of the endowment of Hertford College, told in C.J. Tyerman’s contribution to this project, is so intriguing. Brasenose turned down the Baring endowment because the institution of new denominational fellowships was apparently illegal for one of the existing colleges; but it was not so for new foundations, as Gladstone and others made clear as the bill passed through the Commons; and the key question was whether Hertford counted as a new foundation for this purpose.

Keble College Chapel.

It is striking that the two new men's foundations of the 1870s were firmly Anglican ones, the other one being Keble, which received its Charter in 1870 but, being without an endowment or a fellowship at the time of its Charter was unconstrained by the terms of the 1871 Act and did not admit non-Anglicans until the 1930s. Its first lay Warden took office over a century later, in 1980. So in fact it was Anglicans who first took advantage of the opening to religious pluralism – much more so than the Congregationalists and the Unitarians, whose colleges, when they relocated to Oxford, remained outside the structures of the University. This reflected a shift in attitudes within the High Church party towards the trappings of Establishment. One manifestation of this reorientation was (paradoxically) the institution of the Honour School of Theology in 1869. This had formerly been opposed by Pusey and the High Church party on the basis that theology was, properly understood, the foundation of all university education and not just one discipline among many; but in the face of what they perceived as the secularization of the University, and in particular of the philosophy curriculum in Greats, they saw a separate Honour School firmly in Anglican hands as the best way of preserving the interests of doctrinally sound teaching.

The interior of Keble College Chapel.

How much difference did the 1871 Act make? There were, in fact, a few non-Anglican fellows before 1871: notably Scottish Presbyterians such as James Bryce (Oriel, 1862) and Edward Caird (Merton, 1864). Caird (a future Master of Balliol) was a member of the Church of Scotland, but Bryce was from a secessionist Scots-Ulster Presbyterian background, fiercely opposed to state-mandated religion, and yet that did not prevent his appointment by Gladstone to the Regius Professorship of Civil Law in 1870, before the abolition of tests. In Oxford, unlike Cambridge, there were few instances of promising graduates denied the opportunity of a fellowship by the religious tests. There were plenty of other barriers to a substantial nonconformist presence in Oxford: not least the Anglican character of most of the public schools that were increasing their domination of Oxford admissions in this period. The first English nonconformist elected to a college fellowship in the wake of the 1871 Act was the Congregationalist Robert Horton at New College in 1879, and his father had been criticized by fellow nonconformists for sending his son to Shrewsbury; but the grounding in the classics he acquired there equipped him to win an open scholarship and firsts in Classical Mods and Greats. Roman Catholics, by and large, continued to follow their bishops’ instruction to avoid the English universities, and the first Catholic college fellow was F.F. Urquhart of Balliol, elected a quarter of a century later. His uncle, and de facto guardian, had been a member of Gladstone’s cabinet in 1871, so if this was diversity it was of a very specific kind. The Act itself did not touch the clerical character of Oxford: all college headships (with the exception of Merton) were restricted to Anglican clergy, and the Anglican domination of governing bodies was guaranteed as long as more than half of college fellows were in holy orders or required to proceed to ordination. Tutorships – which were not yet, by and large, distinguished by disciplinary specialism – remained predominantly clerical offices. It was the 1877 Royal Commission that really inaugurated fundamental change, by radically pruning the number of clerical fellowships, removing the clerical restriction from headships, and instituting the practice of electing to official fellowships tied to tutorships in particular subjects.

In short, the 1871 Act, important as it was, did not mark a clean break. The tests, had they remained, would certainly have been an obstacle to Oxford’s evolution into a global university; but clearly less so than the geographical restrictions attached to most fellowships and scholarships before the reforms of the 1850s. And it was the work of the 1877 Commission that was more decisively important in enabling Oxford to enter the world of the research university.

Stuart Jones, Professor of Intellectual History at the University of Manchester.

More from the Blog

Follow us on Twitter here.