Oxford Re-formed

How has the Reformation been commemorated, forgotten, or re-imagined in Oxford over the past five hundred years? We first began thinking about this question when we noticed a memorial on Oxford’s High Street that surprised us. On the front of Oriel College’s Rhodes Building, opened in 1911, is a statue of Cardinal William Allen. A fierce enemy of Queen Elizabeth I, Allen spent his life trying to undo the Protestant Reformation in England. He set up schools and seminaries in Europe to train missionaries and encouraged English Catholics to rebel against their queen by aiding the Spanish Armada in 1588. Why was a statue of this exceptionally controversial figure put up in the centre of early twentieth-century Oxford? Allen was, for a short time, head of St Mary’s Hall which was incorporated into Oriel in 1902; so, his statue signals continuity with the disappearing pre-Reformation past, especially as the College’s surviving medieval quadrangle was demolished to make room for the Rhodes Building.

William Allen statue (By permission of Oriel College, Oxford).

But, as we have discovered, this is not the whole story. The statue also speaks of the many dramatic changes in Oxford since the sixteenth-century Reformations: the nineteenth-century Oxford Movement which sought to return the English Church to its pre-Reformation past and which began at Oriel led by that other English Cardinal John Henry Newman; the arrival and expansion of communities of different faiths in the city and University in the twentieth century, and the transformation of Oxford through the processes of empire and colonialism. As debates about the weight of the past on the present have gripped Oxford and the wider world, this exhibition takes a long view of the contested memories of the Reformation in this history-making city. ‘Oxford Re-formed’ offers a fresh look at Oxford, tracing how from being a Catholic and then a Protestant stronghold, the city has become a home for diverse communities of all faiths and none.

Oxford and the Reformation

Not a single event but a long-lasting process, the English Reformation began in the 1530s. Henry VIII rejected the claims of the pope to rule the Church and closed England’s monasteries and shrines. His son, Edward VI, enforced a still more radical Reformation, using the new Book of Common Prayer to impose Protestant worship and teachings on the nation. Edward’s successor, Mary I (reigned 1553-1558), attempted to restore Catholic forms of worship and belief. Yet this was short-lived. A distinctive Protestant Church emerged under Elizabeth I from 1558. The monarch would govern the Church; the Bible and worship would be in English rather than in Latin; and some traditional beliefs and ceremonies would be suppressed.

The University Church of St Mary the Virgin.

Arguments about what to believe, how to worship, and who should be head of the Church did not cease, however. On the contrary, religious debates and divisions proved almost unending, as did the attempts by different Christian groups to commemorate the battles of the past and to use them to fight those of the present.

The Reformation had global consequences. It prompted religious refugees to flee Europe and motivated missionaries to travel the world – from North America in the seventeenth century, to Africa in the nineteenth. In Oxford, museums, colleges, churches, and homes are all filled with the spoils of empire. Men and women came from the colonies to study here. This globalization helped transform the city and University as mosques, temples, and synagogues took their place alongside churches and chapels. In this sense, too, Oxford continues to be re-formed.

Before the Reformation

The shrine of St Frideswide gives us a glimpse of the world before the Reformation. Then the city was rich in relics and shrines. Many of the university’s most prominent scholars were monks or friars – and almost all the rest were in holy orders too. Their daily routine combined study with worship. Presiding over the university and city was their patron, St Frideswide, an eighth-century abbess.

The shrine of St Frideswide ‘By kind permission of the Governing Body of Christ Church, Oxford’.

St Frideswide’s Priory (now Oxford Cathedral) opened a new shrine to Frideswide in 1180, prompting a protest by a local Jewish man, whose subsequent suicide was attributed by some Christians to the intercession of the saint. The presumed power of the shrine attracted pilgrims for centuries, including Henry VIII’s first wife, Katherine of Aragon, who visited in the hope that Frideswide would help her conceive a son. But Protestant reformers saw such behaviour as mere superstition. This shrine was one of many sites that they destroyed from the late 1530s onwards, along with books, statues, stained glass, and other artefacts. All that now remains of the original shrine is the platform on which it rested.

The question of how the remains of medieval faith should be dealt with by a reformed Church and a Protestant university was never really resolved. Although at one point it looked as though the colleges would be abolished just like the monasteries, they endured, retaining their pre-Reformation buildings, names, and many of their symbols.

Martyrdom and Persecution: Protestant Martyrs

Built nearly 300 years after the events it commemorates, the Martyrs’ Memorial is a great Gothic structure intended to celebrate three men killed for their rejection of the Catholic faith.

During Mary I’s five-year reign (1553-1558) around 300 Protestants were burned for heresy. Among them were Bishops Hugh Latimer of Worcester and Nicholas Ridley of London in 1555, and Archbishop Thomas Cranmer of Canterbury in 1556, after his trial in the University Church of St Mary the Virgin. The burning of these three Protestants took place in Broad Street, Oxford, and the event is commemorated by the Martyrs’ Memorial in St Giles which was designed by George Gilbert Scott and erected between 1841 and 1843. Cranmer is shown holding a copy of the 1541 English Bible. Ridley is dressed in the bishop’s robes that he defended against still more radical Protestants who called them ungodly and popish. Latimer is shown in ‘pious old age’, as he was about 68 at the time of his death.

The Martyrs’ Memorial (Ethan Doyle White, Wikimedia Creative Commons).

The memorial was as much about the Victorians as it was about these Tudor martyrs. The decision to commission the monument grew out of the deep anti-Catholicism of many nineteenth-century Oxford Protestants. They were horrified by the growing religious freedoms allowed to Roman Catholics. They feared that Oxford University, which still refused to admit anyone who was not a member of the Church of England, would soon be forced to change. They wanted to remind the public of the dangers of Roman Catholicism and to assert that Oxford was impeccably Protestant. The inscription on the base is strongly anti-Catholic and refers to the ‘errors of the Church of Rome’. It was a popular claim in a period of on-going anti-Catholicism and the cost of the Memorial was largely covered by private subscriptions.

Martyrdom and Persecution: Catholic Martyrs

This wall-painting, or mural, in the Catholic Church of St Aloysius, on Woodstock Road depicts one of the most famous of Oxford’s martyrs, St Edmund Campion.

St Aloysius Campion mural (Todd Atticus).

When Elizabeth I visited Oxford in 1566, Edmund Campion, a fellow of St John’s College, welcomed her on the University’s behalf. Soon afterwards, however, he left England and became a member of a Catholic religious Order, the Jesuits. In 1580, he returned with two other Jesuits on a secret and dangerous mission – by this time Elizabeth had been excommunicated by the Pope who also called for her deposition. In Catholic houses, Campion preached and celebrated the Mass. In Oxford he had copies of his pamphlet ‘Ten Reasons’ [Rationes Decem], explaining why he could not be a Protestant, provocatively placed in the University Church of St Mary the Virgin. Both these actions were illegal in a Protestant state which insisted on seeing Catholicism as treason.

Following his capture, Campion was tortured, condemned for treason, and then in December 1581 executed. This mural tells the story of his life from his time in Oxford to his death in London. Here he is depicted standing before Queen Elizabeth in 1566, writing in Rome, travelling back to England, and then being hung, drawn, and quartered. Campion was made a saint by the Catholic Church in 1970. He was one of some 300 Catholics who died on account of their faith in the reign of Elizabeth I.

Restoration Orthodoxy and Dissent

Almost the first building ever designed by Christopher Wren, the Sheldonian Theatre is the principal ceremonial hall of the University. It was paid for by Gilbert Sheldon (1598-1677), then Archbishop of Canterbury. The ceiling is the work of Robert Streater, court painter to Charles II, and depicts ‘Truth Descending upon the Arts and Sciences to expel ignorance from the University’. This was more than a straightforward celebration of the power of learning, however. It symbolized the way in which those outside the Church of England were excluded from Oxford.

Sheldonian detail (By Permission of the Sheldonian Theatre and IFACS (International Fine Art Conservation Studios)).

The ongoing conflict over the religious settlement in England, Scotland, and Ireland culminated in the Civil Wars of the 1640s, during which Oxford was the headquarters of the King. In 1646, the bishops were abolished, and, after Charles I’s defeat and execution in 1649, Church and state no longer enforced the use of the Elizabethan prayer book nor were people required to attend their parish Church by law. But the subsequent proliferation of religious and political ideas seemed frightening to many, and with the return of the monarchy in 1660 bishops were restored and a new Prayer Book authorised. Many Protestants simply could not accept either, and these ‘Dissenters’ were expelled from the Church of England and from the University, along with the previously excluded Catholics. The Sheldonian Theatre was built as a monument to this particularly exclusionary moment in the history of the University and the Church, one largely engineered by Archbishop Sheldon. In the years that followed, many would seek to reform this settlement. But it would not be until the nineteenth century that the University reopened its doors to those outside the Church of England.

The Oxford Movement

Keble College looks different from much of the rest of Oxford. It was meant to. Striped brick instead of stone symbolizes a new sort of institution: one that tried to reform Oxford by returning to older ideas about faith and education. The college was founded in 1870 as a memorial to John Keble, a poet, priest, and leading figure in what was known as the Oxford Movement. The members – called ‘Tractarians’ because of the voluminous tracts they wrote - believed that the Church of England had been undermined by aspects of the Reformation. They were also passionate critics of what they saw as the lacklustre religion and loose morals of modern Oxford.

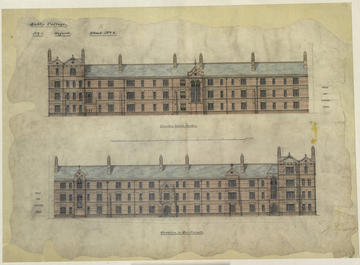

Keble plans (Keble College, Oxford, UK / By Kind Permission of the Warden, Fellows, and Scholars of Keble College, Oxford / Bridgeman Images).

Like everything the Oxford Movement did, the foundation of Keble was an attempt to recapture something that they believed had been lost. Even its architecture looks far back into the past for inspiration, combining influences from the Middle Ages and Byzantium. But for many of their critics, this attempt to recover aspects of the pre-Reformation Church looked dangerously like the return of Roman Catholicism. The decision of a small number of Tractarians to leave the Church of England for Roman Catholicism served to fan the flames of these suspicions and fears. The College had become the focus for huge ambitions but also deep dislike.

Catholic Return

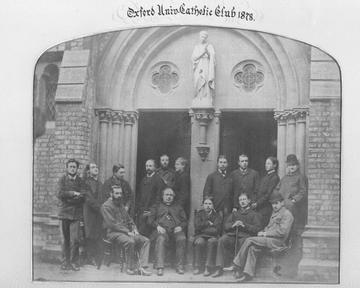

This photograph shows a group of men sitting outside the Catholic Church of St Aloysius around 1875, when the church was completed. Among them is the poet and Jesuit priest Gerard Manley Hopkins (1844 – 1889). Born a member of the Church of England, he was one of several late Victorian Oxford graduates who converted to Roman Catholicism: a change that led to fury from his family and some of his friends. Returning to Oxford as curate of this newly built church, he became a founding member of the Oxford University Catholic Club, later renamed the Newman Society, after John Henry Newman, former vicar of the University Church, who had also left the Church of England for that of Rome.

Hopkins photo (By permission of Campion Hall, Oxford).

Although not published till after his death, Hopkins’s experimental and vivid poetry, which meditates on faith, love, and the beauty of the natural world, evokes the Oxford of the nineteenth century. Yet, even if his poetry is unique, Hopkins’s life was not so unusual. There were several high-profile conversions to Roman Catholicism in Oxford in the Victorian period. Many contemporary Protestants were appalled to find that Oxford, intended to be a bastion of the Church of England, seemed now to encourage such change. At the same time, new Catholic communities arrived in Oxford, which led to the construction of Catholic churches including St Aloysius.

Members of the Catholic Church were excluded from full civil rights until reforms of 1791 and 1829 gradually restored most of their freedoms. It took until 1854, though, before they could study for a degree at the University of Oxford. Fearing the influence of a Protestant education, the Pope formally banned them from joining until 1896. Even before that, however, Catholics had begun to make their presence felt, as this photograph shows.

Absences

This statue of John Henry Newman (1801 – 1890) by Léon-Joseph Chavalliaud stands outside the Brompton Oratory, the London home of the Oratorians, the religious order, founded in sixteenth-century Rome, that Newman had joined after leaving the Church of England. Yet the statue was originally intended for Oxford because of the widespread respect for Newman’s literary as well as ecclesiastical status. The outrage this proposal provoked from those who saw it as an insidious attack on Protestant Oxford and a defiant response to the Martyrs’ Memorial forced a change of heart. The statue was installed in London instead. This late Victorian storm demonstrates the ongoing tensions the Reformation provoked. It also, however, draws attention to the many places and people who are not commemorated and who still find no place in Oxford.

Statue of John Henry Newman, Brompton Oratory, Kensington (Jennette Russell, Art UK).

Newman is an especially telling absence. A devoted evangelical member of the Church of England in his youth, he implacably opposed equal rights for Catholics and sought to defend the University as a stronghold of the Protestant Church. He was a leading figure in the Oxford Movement and, as Vicar of the University Church, he was known as the most able preacher in the city. Yet doubts came to assail his confidence in the Church of England. In 1845, he was received into the Roman Catholic Church, becoming a Cardinal in 1879. In 2019 he was formally canonised and made a saint. For many Victorian Protestants, he was proof of all that could go wrong at Oxford. Little wonder so many at the time opposed his memorialization.

Oxford Opens Up

The dominance of the Church of England was slowly eroded across the nineteenth century. This was the result of pressure from outside and reformers from within. It was a change symbolised by the foundation of new sorts of institutions for new kinds of students: Non-Conformist Protestants, Roman Catholics, women, and people of all faiths and none. Manchester College, now Harris Manchester, for Unitarians was one; non-denominational Somerville founded for women in 1879 another.

Harris Manchester College (Deanna Mccombs).

The Days of Creation windows at the Unitarian Manchester College, designed by Edward Burne-Jones, caused a storm within the denomination, one puritanical member condemning these ‘idle women shuffling along with fantastic robes and gaudy wraps of impossible feathers, doing nothing but make eyes at those who court them.’

At Somerville, Cornelia Sorabji (1866 – 1954), an Anglican from India was one of those able to take advantage of Oxford starting to open up to women. She was the first woman to study law at Oxford and the first female advocate in India.

Both Manchester and Somerville represented the arrival of forces that many members of the Church of England had sought to exclude. Unitarians, who questioned the idea that God was best understood as a Trinity of Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, were regarded by many as scarcely Christian at all. There were some clerics who likewise doubted the wisdom of female higher education. ‘Inferior to us God made you, and our inferiors to the end of time you will remain’, declared one in an ‘Address to the women of Oxford’ in 1884. There were also those who welcomed the arrival of women but doubted the wisdom of a non-denominational college. In every way, Manchester and Somerville symbolise a new dispensation for Oxford.

Oxford and the World

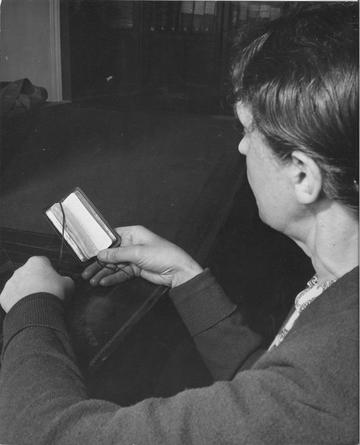

This tiny book is printed on a remarkable new kind of paper invented in the nineteenth century. Oxford India paper, first used to print the Bible in 1842, was the outcome of what has been described as the University Press’s ‘obsession’ to produce ever thinner paper and ever smaller and more portable books. The origins of this incredibly thin yet strong new material are still shrouded in mystery – although it seems that it was inspired by advances in paper technology from East Asia. What is clear is that it helped Oxford University Press to flood the empire with scripture. Many missionaries were sent out from Oxford too – and returned with materials and artefacts from the lands whose peoples they intended to convert to Christianity.

The India Bible (By permission of the Secretary to the Delegates of Oxford University Press).

The impact of the empire on Oxford can be traced in many monuments. The Indian Institute on Broad Street was intended to educate the civil servants and missionaries who would run the subcontinent. Rhodes House was meant to accommodate the leaders of the ‘Anglo-Saxon race’. Now highly controversial, the material remains of empire continue to haunt Oxford and - whether in the stained-glass windows commemorating imperial heroes or in the collections amassed by missionaries – it is almost impossible to separate them from the religious history of the city.

Oxford Today

The Cowley Road Carnival is held each year to celebrate the diversity of modern Oxford. The origins of those who participate can be traced across the whole world – people of many different cultures, ethnicities, and faiths. This multi-cultural presence in Oxford has changed the city and University. Mosques, temples, and a Jewish Centre which houses a synagogue, library, study rooms and a social space, have transformed the physical landscape of the place in the twentieth- and twenty-first centuries.

Cowley Road Carnival (Anthony Morris, Farmoor, Oxford).

Yet, with its chapels and choirs, its ancient monuments, its many churches, and its dreaming spires, Oxford abounds in Christian presences. The memorials and the many homes for seven Christian denominations, each bear witness to the on-going importance of the Reformation. But now they also contribute to the pluralism of the place – a pluralism that includes people of all faiths and none.

Oxford Re-Formed launched on 13th January 2022 on the Museum of Oxford Digital Exhibitions website. The exhibition explores the evolution of the visual and material traces of the Reformation in Oxford’s cityscape, showcasing public buildings and monuments, as well as artefacts that are not usually on public display.

Click here to view the exhibition online.