Samuel Alexander and Jewish Philosophy at Oxford

‘A Jew has been elected to a Fellowship at one of the colleges of the two Universities for the first time since the passing of the Test Act … and should now be welcomed among us as an honour to the whole Community’, reported the Jewish Chronicle on 5 May 1882. The paper’s historic announcement heralded the election of an Australian-born philosopher, Samuel Alexander, to a fellowship at Lincoln College, Oxford. Alexander’s admission to the University marked a significant moment in the gradual dissolution of the closed Anglican corporation which had lasted for undergraduates until 1854, and for fellows, professors, and heads of house until 1871. Not solely Alexander’s religious background, but also his philosophical inclinations expressed his relative distance from Oxford’s traditional academic culture: a distance which the reforming University proved capable of accommodating only in part.

Samuel Alexander. Reproduced with permission of Lincoln College, Oxford.

Alexander’s upbringing and early formation reflected the ways in which the coming of railways, telegraphs, and steamships was tending to break down Oxford’s Tractarian-era insularity in favour of closer connections to the wider world. Born in Sydney in 1859, Alexander grew up mainly in Melbourne, where he attended Wesley College. Wesley’s headmaster, Martin Irving, was the son of Edward Irving, the founder of the Irvingite millenarian sect: Alexander later wrote that his future teacher was the baby boy whom Thomas Carlyle recalled in his Reminiscences (1881) having seen in the Irvings’ London household. It may have been the influence of his headmaster, a former member of Balliol College, that led Alexander to set out for Oxford to try for an undergraduate scholarship in 1877. He won a classical scholarship to Balliol, beating George Curzon to that distinction. Alexander would subsequently coach Curzon for his disappointing Second in Oxford’s Honour School in Literae Humaniores, or ‘Greats’. Expecting to have to pursue a legal career, Alexander’s successful performance in the fellowship examination held in the Lincoln College hall on 21 April, 1882, instead spared him to philosophy.

The dining hall of Lincoln College, Oxford.

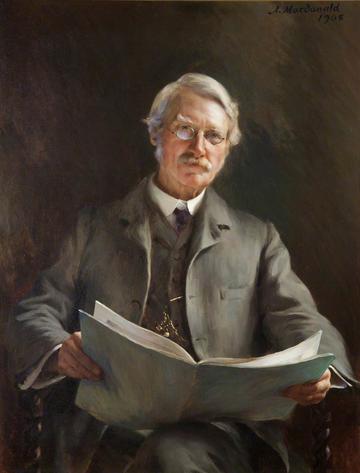

Lincoln’s decision to elect Alexander reflected the liberal majority in religious questions amongst its small society of twelve fellows, of whom approximately half resided in Oxford. The College’s secular Anglican Rector, Mark Pattison, was one of the sharpest scourges of ecclesiasticism in university affairs and Victorian intellectual life. At around the time of Alexander’s election, Pattison was engaged in a struggle with the College’s visitor, the high church bishop of Lincoln, Christopher Wordsworth, to implement a laicising revision to the College’s 1856 statutes. They still required ten of the fellows to proceed to Holy Orders within ten years of their election. In a debate held in the House of Lords on 12 May, 1882, the visitor secured the annulment of the statutes, which in the end were not revised until 1926; but the failure appears not to have jeopardised Alexander’s status in the college. In later years he always looked back on his time at Lincoln with fondness. ‘We were a fairly happy family, and on terms of great personal kindness with one another’, he later wrote in an autobiographical letter. With the humanely observant humour that was one of his characteristics, he also recalled that the practice of fellows’ breakfasts had fallen into desuetude after the Roman historian and ornithologist, Warde Fowler, once flung a loaf at the wall ‘of our dignified Common Room’, during a surprising outburst over the quality of the College’s food.

Portrait of William Warde Fowler by Alexander MacDonald. Lincoln College, Oxford.

Though personally content at Lincoln, Alexander’s philosophical agenda placed him at variance with the conventional Oxford philosophy of his day. Teaching at a time when philosophy was studied as part of Classics, as would remain the case until after the First World War, Alexander became gently frustrated at the ways in which this tradition, in his view, cut Oxford philosophy off from new departures in the study of the subject. During Alexander’s youth, philosophy at the University – as at numerous other universities in Britain and the United States – was dominated by Idealism, a Hellenistic and Hegelian mode of thought which maintained that reality was ultimately mental or spiritual in nature. Idealists held that the highest task of philosophy was to bring mind to a consciousness of its ultimate unity. Alexander’s first book, Moral Order and Progress (1889), signalled his developing departure from Idealist moral philosophy, an approach which privileged the philosopher’s examination of the data of conscience, in favour of a self-consciously ‘scientific’ ethics much more grounded in biology and psychology as the means of weighing moral problems. This mode of thought, owing a debt to the agnostic philosopher, Leslie Stephen, was a fairly common one amongst relatively advanced thinkers of Alexander’s generation; but Oxford was not at that time the place to develop its implications.

Toynbee Hall, c. 1902.

Alexander began to spend more and more time away from the University, studying with the pioneer of experimental psychology, Hugo Münsterberg, at Freiburg im Breisgau during the winter of 1890 to 1891. Politically a non-partisan, left-wing radical, he came to prefer the bracing atmosphere of university extension lectures in London to the quieter comforts of the termly tutorial round. He joined a number of the Oxford dons of his generation in teaching philosophy to working-class learners at Toynbee Hall, a radical settlement in London’s East End. He also spoke at meetings of the ethical societies spreading in British towns and cities at around the turn of the century, amidst a growing public interest in the cultivation of scientific and unsectarian moral debate.

The John Owens Building, c. 1908.

Alexander’s intellectual ambitions and progressive sympathies led him to accept an 1893 offer to become professor of philosophy at Owens College, soon to be reconstituted as the University of Manchester, where he would continue to work until his retirement in 1924. Alexander’s early disenchantment with Idealism led him to develop a new approach to metaphysics. To modern posterity, the waning power of British Idealist philosophy around 1900 is usually associated with George Edward Moore’s and Bertrand Russell’s cultivation of analytic philosophy, with its close attention to the meanings of concepts as part of the theory of knowledge. But Alexander’s own alternative to Idealism took the form of a ‘realist’ theory of the ultimate nature of things, which began to take shape in his writings from around 1900. Influenced by Henri Bergson’s philosophy of time, and Albert Einstein’s theory of relativity, Alexander became especially interested in the significance of space-time – or the discovery that space and time existed not separately but on a kind of continuum - for the reconstruction of metaphysics.

Alexander’s many years of research in the field culminated in his 1917-18 Gifford Lectures, a Scottish foundation dedicated to natural theology, which he published in two volumes as Space, Time, and Deity (1920). In Alexander’s account, previous philosophies had regarded time as an after-thought, a kind of extension of reality. But for Alexander, space-time was really the unity within which all phenomena, mental and physical, had their being. Mind was not a self-contained ultimate reality, as Idealists had held. Rather it was a new quality of existence which emerged out of, and existed in interaction with, the physiological processes of sense and cognition intelligible in the light of experimental psychology, all unfolding within the higher unity of space-time. Thus, Alexander did not regard himself as proffering a materialist theory of reality. Rather, minds and things developed within the process of space-time in ways that gave rise to progressively higher qualities, albeit always with the potential of shrinking back into lower stages. The higher quality above the highest quality yet attained, Alexander considered, was God.

Alexander's Gifford Lectures were printed in a two-volume publication in 1920.

Space, Time, and Deity prompted admiration and engagement across Britain and overseas. Some regarded it as the greatest work of English metaphysics since Hobbes’ De Corpore of 1655. Alexander’s metaphysical system garnered attention in a philosophical and intellectual world still attuned to the quest for finding spiritual meaning and reassurance in the processes of history, albeit within different frameworks from those which had appealed to nineteenth-century intellectuals. Alexander’s metaphysical efforts would lose their appeal further into the more cynical climate of the later twentieth century, compared to the enduring popularity of the common-sensical bite of the analytic philosophy which had originally developed in parallel to them. Alexander had numerous contemporaries in his attempts to resolve the dualisms of modern life; but less of an academic posterity after 1945.

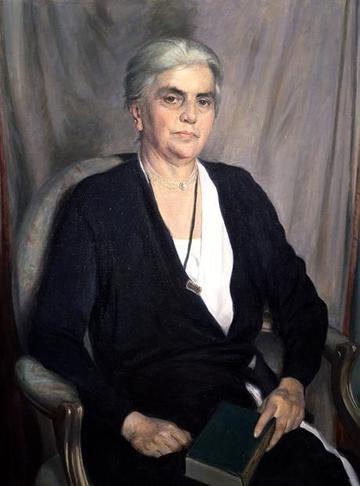

Portrait of Eleanor Rathbone by James Gunn.

Though prone to bouts of the philosopher’s melancholia, Alexander’s cheerfully good-humoured and public-spirited attitude to his work touched many circles of life. Never marrying, he maintained a sociable household before and after his Australian family came to live with him from 1902. He acquired a dog, Griff, short for Begriff or ‘concept’, about whom he wrote an article on ‘The Mind of a Dog’ for the Cornhill magazine in 1906. Alongside his academic work, he supported women’s suffrage campaigners in Manchester; and backed the Liverpudlian social reformer, Eleanor Rathbone, in her successful candidacy for the Combined English Universities seat in 1929. Alexander’s later years brought him many honours. At the instigation of Warde Fowler, Lincoln College elected him an Honorary Fellow in 1918; and aided by a decades-long rapport with Ramsay MacDonald stretching back to his London lectures, he became a member of the Order of Merit in 1930. A distinguished, if not a closely-involved, member of Manchester’s Jewish community, he was buried in the section reserved for the British Jewish Reform Congregation at the Manchester Southern Cemetery after his death on 13 September, 1938. His will left most of his financial legacy to Manchester University.

Southern Cemetery, Manchester.

How far was Alexander’s Jewishness important to his work as a philosopher? The relevance of Alexander’s faith to his philosophical arguments is a debatable point. His relative disconnection from the liberal Anglican and Presbyterian anxieties which sublimated older Christian Platonism into late-Victorian Oxford Idealism may have made him readier than his gentile contemporaries to break with Idealism’s guiding assumptions in favour of a realist philosophical stance. At the same time, there was nothing inherently ‘Jewish’ in Alexander’s post-Idealist reinvention of the spiritual meaningfulness of time. This was not an unusual step amongst the religious philosophers of his generation, even if Alexander pursued that inclination to a uniquely systematic extent. But before Jewish audiences, Alexander himself stressed the Jewish ancestry of his philosophy. In a lecture to the Jewish Historical Society in London in 1921, Alexander presented his metaphysics as a kind of completion of Spinoza’s ontology in the light of the theory of space-time, which, Alexander thought, could save Spinoza’s system from its latent error of treating the existing universe as though it were God. Space-time was not itself God, according to Alexander, but rather contained a nisus, or effort, which pointed beyond itself to a personal deity worthy of worship. At the close of his lecture, Alexander considered that he ‘may take pride in showing his affiliation to such a philosopher as Spinoza, and the more if he is himself a Jew speaking to Jews’. Alexander’s Judaism appears to have become more important to his public, and perhaps also his private self as he grew older. The generally happy pattern of Alexander’s life, lived out in the comparative tolerance of English peace, darkened in his final years as he saw his people begin to fall victim to the hatreds of the twentieth century. A friend of Chaim Weizmann, who was for a time an academic biochemist at Manchester, his growing awareness of the limits of Jewish assimilation to European societies led him to become a Zionist. He introduced Weizmann to Arthur Balfour and made donations to the Palestine Foundation Fund. Accruing personal wealth through his simple habits, he gave much of it away to support refugees to Britain from Nazi Germany and Austria. His will left £1000 to the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

The Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

Although Alexander’s philosophical and personal development took him away from Oxford at a relatively early point in his career, he remained amicably connected to the University; and the study of philosophy and psychology at Oxford gradually moved in directions of which he would have approved. In a letter he wrote to the editor of the American Journal of Psychology in 1887, Alexander expressed the hope that ‘before long we may, I trust, have a laboratory for experimental psychology’ at Oxford. After a certain delay, Oxford acquired a graduate institute of experimental psychology in 1936. Alexander’s arrival at Lincoln College thus instantiated the ways in which in which a growing diversity of background helped to foster a new diversity of thought in the late-Victorian university. It is a pattern which has not lost its vitality or relevance in the intervening century and a half.

Joshua Bennett, Darby Fellow in Modern History, Lincoln College, the University of Oxford.