Dambudzo Marechera and Oxford’s “Kiplingesque imperialists”

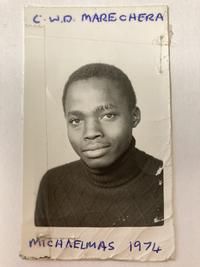

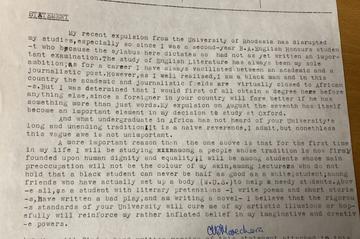

Dambudzo Marechera, a twenty-year-old Black student from Zimbabwe, arrived in Oxford on 4 October 1974 to study English Literature at New College. He had no money and no possessions other than the clothes he was wearing that day. A ‘native subject of the British colony of Rhodesia’ (under white minority rule at the time), Dambudzo had recently been expelled from the University of Rhodesia for leading student protests. Upon joining the University of Oxford, he hoped to study ‘among a people whose tradition is now firmly founded upon human dignity and equality,’ as he said in his application statement.

Figure 1 Matriculation picture upon arriving to New College.

Figure 2 Statement of purpose for his application to Oxford.

Sadly, things quickly started falling apart. Marechera, who was then called by his Christian name, Charles, felt deeply alienated and unhappy in Oxford, a place he both worshipped and wanted to burn down, according to his editor James Currey. Although some of his essays were beautiful, highly original pieces of writing, Marechera struggled to adapt to academic constraints, often skipped classes and seldom spoke to his professors or peers during tutorials. ‘I have no complaints, but I am baffled’ said Prof. Pamela Busby on her report card for Marechera. A persisting stammer, which he developed in his childhood following the untimely death of his father, symbolized his difficulty to communicate, and increased his frustration and self-loathing. His scholarship, funded by the JCR of New College, may have paradoxically contributed to his misery: where students expected gratitude and compliance, Marechera offered hostility and resentment at being made to feel like a beggar. At the same time, these challenges fed his creativity: ‘I was learning to distrust language, a distrust necessary for a writer, especially one writing in a foreign language,’ he wrote about his speech impediment in ‘An interview with himself,’ which is the opening text of The House of Hunger.

Figure 3 The House of Hunger (Heinemann, 1987), Marechera’s first novel, won The Guardian Fiction Prize.

Figure 4 Black Sunlight (Heinemann 1980) was banned in Zimbabwe for its "Euromodernism".

Figure 5 The Black Insider (Baobab Books, 1990) is a collection of poems and short stories. It was published posthumously in Harare.

If challenging literary conventions was later to become one of the most celebrated aspects of his literary works, challenging academic and social rules and laws in Oxford did not come without consequence. An avid reader and compulsive book-buyer, Marechera was tried by the County Court for the non-payment of his debt to Blackwell. He suffered from a devastating alcohol addiction, sometimes physically assaulted the staff and students of New College, and tried once to set the college on fire. Marechera was also an outsider within the African student community in Oxford. Jane Bryce reports a surreal scene during which Marechera read some of his poetry to the MCR in New College: several African students in the audience berated his poetry for being individualistic, pessimistic, and not contributing to anticolonial struggles and sentiment. To which Damdubzo flamboyantly replied: ‘I will not tick the orifices of political correctness (…). If you expect me to be a writer for a specific nation or a specific race, then f**k you!’ He then threw a massive ashtray through a window, causing panic and mayhem throughout the room and quad. Beyond violence, Marechera carved a unique path against both cultural nationalism and neocolonialism. His short story ‘Oxford, Black Oxford,’ published in Black Insider, makes clear his disgust for the obscenely privileged cliques of British aristocrats at the University of Oxford. Norman Vance, one of his tutors, remembers Marechera bursting into his room in New College one night, screaming: ‘You are all Kiplingesque imperialists!’

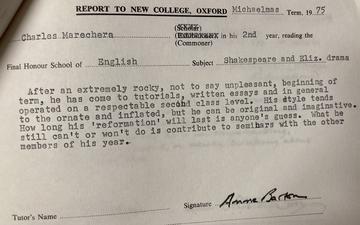

Figure 6 One of Marechera's student reports during his second year at Oxford.

Not fitting anywhere, Marechera’s intelligence, charm, and devotion to literature were nonetheless noted by all. He was always carrying a large stack of books under his arms and was widely read in European classical and modern literature. While studying Romanticism in the beginning of his second year, he became obsessed with the atheist and rebellious poet Percy Shelley, who loathed the University’s conformist conservatism. Shelley was expelled from Oxford in 1811 after writing his infamous pamphlet, The Necessity of Atheism.

Marechera’s unique and uniquely challenging personality resulted from the intersection of tragic political and family circumstances: from a destitute background in Rhodesia, his exceptional abilities won him scholarships that allowed him to gain the best possible education for a Black subject at the time. When he lost his father at thirteen, Rhodesian laws prevented Dambudzo’s mother and her nine children from staying in their house in Rusape. The family was evicted, and his mother lost her job. She started heavily drinking and engaged in prostitution. At the same period, Dambudzo began suffering from hallucinations and paranoia, for which he was medicated. He preferred the comfort and stability of his Christian boarding school to the chaos and destitution of his home, while deeply loathing the structural racism embedded in his everyday existence. He also struggled with guilt towards his younger siblings, who lived in extreme deprivation. Mental illness as well as alcohol addiction plagued Marechera his whole life. In Oxford, he was advised to commit himself to a psychiatric hospital, which he vehemently refused.

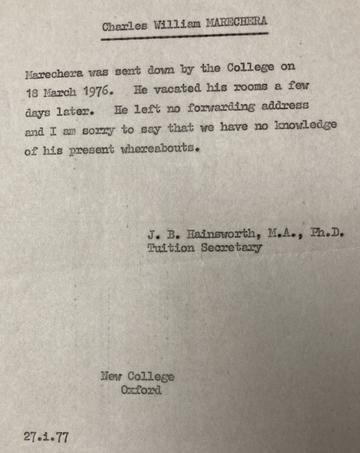

Figure 7 A letter (probably in response to an enquiry) from New College about Marechera, ten months after he was sent down from the University.

Despite the support and patience of New College’s warden William Hayter, of his wife, Lady Iris as well as that of some of his professors and friends, Marechera was eventually sent down from New College in March 1976. He left his room a few days later and became a vagrant in Oxford and then London. He published the acclaimed novel The House of Hunger with Heinemann in 1978, which went on to win The Guardian Fiction Prize, but kept living a bohemian life of excess and destitution. He returned to independent Zimbabwe in 1981 and realized that he did not fit in better in his home-country than he did in England. Indeed, his second novel, Black Sunlight, was banned by the Zimbabwean government for its supposed ‘Euromodernism,’ which was deemed incompatible with the country’s nation-building process. Dambudzo Marechera lived as a vagabond and an outsider in Harare, regularly locked up by the Zimbabwean police. He kept on writing and publishing plays, poetry, prose and essays. He died of AIDS in 1987, at thirty-five years old. Leaving behind some of the most original and powerful works of African postcolonial literature, some published posthumously, Dambudzo Marechera is considered an essential and unique African voice, who carved a non-conformist path between structural racism, the politics of liberation and creative autonomy.

Dorothée Boulanger, Leverhulme Early Career Fellow in Modern Languages and Junior Research Fellow at Jesus College, Oxford.

*I am grateful to Jennifer Thorp, New College Archivist, for letting me consult Dambudzo Marechera’s student file at New College and take the pictures illustrating this article