The English pride themselves on their tolerance, none more so than members of the Church of England. Many have constructed a story of their sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Reformations as a carefully-reasoned preparation for a particular synthesis called ‘Anglicanism’, reasonable, tolerant, well out of reach of any foreign pollution and not susceptible to ready identification with any other ‘ism’. The implication of this is that Anglicanism is sui generis, and that in some mysterious or mystical way, this was the intention of the Tudor monarchs, churchmen, and statesmen who founded it. In fact, the history of tolerance in the English Church is not what it seems, and in much of the story, is entirely lacking.

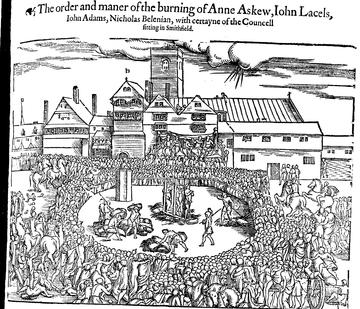

The Protestant Anne Askew was burnt at the stake together with John Lascelles, Nicholas Belenian and John Adams in 1546. This woodcut appeared in the ecclesiastical history and martyrology of John Foxe (1516-1587), Actes and Monuments 4thedition (London, 1583), 1240. Source: Early English Books Online.

The English Reformation already moved away from Luther in Henry VIII’s reign and then took on an unmistakeably Reformed Protestant mould under Edward VI (1547-53). At that stage, its links were first with Strassburg and then with Zürich, but by the time of Elizabeth I’s accession (1558), John Calvin and Geneva were generally more dominant in European Reformed Protestantism. Meanwhile Elizabeth established her Religious Settlement in 1559, in close cooperation with a close-knit circle of advisers and a strong body of opinion in the secular political nation, though without any popular convulsion like Reformed Protestant activity in France, Scotland, and the Netherlands.

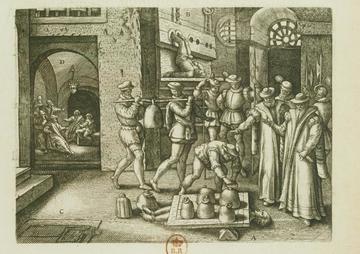

Margaret Clitherow was pressed to death for refusing to enter a plea after her arrest in 1586 on a charge of harbouring Catholic priests. Illustrated in a martyrology by Anglo-Dutch exile Richard Verstegan (1550-1640), Theatrum Crudelitatum Haereticorum Nostri Temporis(Antwerp, 1587), 77. Source: gallica.bnf.fr / Bibliothèque nationale de France.

This Settlement proved much more static than its Edwardian predecessor, and its preservation of cathedrals was very significant in nurturing a ‘High Church’ tradition in the future. Yet it was also created by Nicodemites – people like the Queen herself, who had hidden their real religious opinions in times of repression. Reflecting that, its own repression of both Catholics and Protestant separatists and radicals could be savage but was patchy. Zürich influence continued in England, and the Zürich leadership increasingly allied themselves with English bishops against Puritan critics, whom they regarded as agents of the rival Reformed power-house of Geneva. The Zürich leader Heinrich Bullinger (1504-75) was made an honorary Englishman when from the 1570s, the anti-Puritan bishops led by Archbishop John Whitgift used an English translation of his great sermon collection the Decades as the official textbook for clergy training.

That says something important about the official Elizabethan Church. It was not as yet Anglican: it was a Church still fully part of the Reformed Protestant world, and able to claim this identity because it drew on Bullinger as an alternative to Calvin and Beza. Richard Hooker (c. 1554-1600) was an innovator in his arguments with Puritans, but his irenic style was not that of a newly-aggressive High Church group that developed around Archbishop William Laud (1573-1645). The English Civil Wars (1642-48) partly provoked by Laud’s exclusivity led not only to the execution of Charles I (1649) but also to the establishment of a broad-based national Church under Oliver Cromwell (1599-1658) and even the readmission of the Jews to England in 1656. Yet the restored monarchy of Charles II in 1660 brought a new self-consciously episcopal ‘Anglicanism’, much more narrowly-defined than the pre-war episcopal Church of England. It excluded Protestant ‘Dissenters’ but despite some fierce repression, failed to suppress them, and thereby gave rise to a grudging religious toleration, confirmed by legislation after the arrival of William III in 1688. As a result, the Church of England has grown steadily less able to assert its monopoly role in the nation: That is not to be regretted.

Diarmaid MacCulloch, Emeritus Professor of the History of the Church, University of Oxford.