The Opening of Oxford to the Jews

Jews had not been totally excluded from the University of Oxford before the passing of the 1871 Universities Tests Act. After the readmission of Jewish people into England in the mid-1650s, Hebraists in the University wished to employ Jewish scholars, preferably those who were converts to Christianity, to translate difficult Hebrew texts accurately into Latin. The first practising Jewish Hebraist at Oxford was the Spanish-born Isaac Abendana who in 1689 was appointed a lecturer in Hebrew at Magdalen College, a position he held until his death ten years later. Abendana had previously - from 1662 or 1663 - been employed at Trinity College, Cambridge to teach Hebrew and translate the Mishnah (the Hebraic core of the Talmud) into Latin. While in Cambridge, he had developed connections with Oxford through his sale of Hebrew books to the librarian of Bodley, and he was picked up by Magdalen College a few years after his monumental translation of the 63 tractates of the Mishnah was completed.

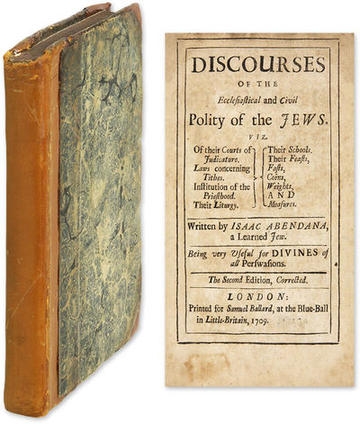

During his time in Oxford, Isaac Abendana wrote a series of Jewish almanacs which were later collected and printed in book form as the Discourses on the Ecclesiastical and Civil Polity of the Jews.

Abendana was unusual in that he never converted to Christianity, despite considerable pressures, unlike the Hebraists Philip Levi (d. 1709), Salomon Israel and David Ahoab. The only other practising Jew at Oxford after Abendana seems to have been ‘Aaron, an old Jew’ who was teaching at Magdalen College between 1726 and 1734. In the 18th century the study of Hebrew declined at both Oxford and Cambridge Universities, and for that reason Edward Gibbon, up at Magdalen in 1752, was dissuaded from pursuing Hebraic studies by his tutor. Nonetheless, Jews, whether professing or converts, continued to teach Hebrew at Oxford. However, they were not fellows and had little status. At the same time, no professing Jew could matriculate at the University because of the Test Acts.

When Jews began to agitate for their emancipation, their exclusion from Oxford and Cambridge was not a priority. Instead, they focussed on admission to the professions, relief from taking oaths before voting (1835), and on the right to sit in parliament (1858). Presumably this was because by the mid-nineteenth century they were not denied access to higher education. Jews could study, graduate, and become academics at University College London (founded in 1826) and other newly established Victorian universities. Added to this, neither Oxford nor Cambridge Universities had the reputation for brilliant scholarship that they enjoy today. Far from it, many contemporaries viewed the two ancient institutions as backward-looking and dominated by an Anglican clerical clique, which indeed for the most part they were!

University College London.

Few Jews initially took advantage of the 1854 Act that allowed them to matriculate, study, and graduate at the University of Oxford. It was only in 1869 that the first Jew, David Frederick Schloss, was elected to a scholarship (at Corpus Christi College where he won a first class in Literae Humaniores). To some extent, there was a lack of applications, but additionally the University found ways to bypass the 1854 Act and continued to discriminate against Jews as with other non-Anglicans. Cambridge may have been more welcoming – after all it was used to Jews studying there even if they had not been able to take degrees – and in the aftermath of the 1856 Act that allowed Jews to graduate there, more Jews entered its precincts. One of them, Numa Edward Hartog, was the first Jew to become the Senior Wrangler (the top mathematics undergraduate) in 1869.

Hartog, however, could not be admitted to a fellowship at Trinity College, Cambridge, despite it being customary for men who were top of their year to be almost automatically elected. Antisemitism played no, or very little role, in this prohibition. The Universities’ strong opposition to removing religious restrictions stemmed from a concern to defend the Church of England from other Christians. In Oxford, men such as Dr Pusey and the Tractarians feared the Church of England was in mortal danger from Dissenters, while many others believed it needed protection from Roman Catholics. No-one believed that the Church needed defending against Jews; and why should they? Jews were a small community in England, and their religion did not seek to proselytise.

Because the two Universities and many colleges persisted in closing their doors to non-Anglicans, the state again decided to intervene. Private members bills were introduced into parliament during the mid-1860s to close the loopholes in the earlier statutes and extend their provisions. By the time William Gladstone’s Liberal government took office in 1868, the arguments in support of such legislation were considered ‘an old story’. Nevertheless, the arguments had to be restated because loud voices were heard in opposition to the Universities Tests Bill, especially in the House of Lords. Those opposing it did not target Jews. As recorded in Hansard, their objections were that ‘the effect of the removal of existing disabilities would be to introduce a great deal of theological controversy into the Universities’ and that these ancient Universities should not suffer state interference as they were not national institutions but ‘special institutions held in trust for a particular denomination’.

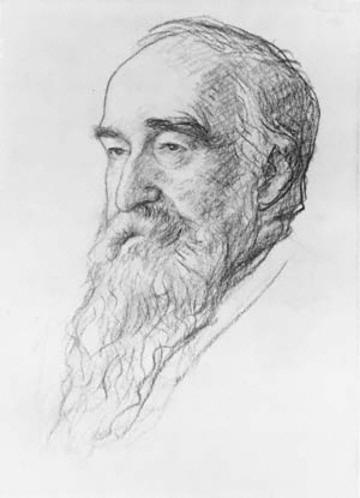

James Joseph Sylvester.

Nonetheless, Hartog’s case played into the hand of the bill’s supporters. In several speeches, members referred to his denial of a fellowship. Another MP claimed that this was ‘no isolated case’ and spoke of a Jewish friend of his (an allusion to the mathematician James Joseph Sylvester) who had been the second Senior Wrangler in his year but was rejected by Cambridge and consequently ‘had to win bread for himself as an actuary in an insurance office’. The human story of Hartog also inspired Jews – previously fairly indifferent to the disability - to come out in support of the bill. Jewish communities from all over England drew up petitions which they presented to parliament at the time of its second reading in May 1870.

After the Lords had twice rejected the bill in 1870, Hartog himself appeared on 3 March 1871 before a select committee of the House of Lords established to inquire into 'university tests'. It has been claimed that his testimony made the Lords change their minds, but this is most unlikely. The Lords caved in partly because Gladstone had thrown his weight behind the bill in 1871, and partly because the Anglican perception was growing that Dissenters were benefitting from the publicity as opinion was swaying in their favour. It should also be recognised that together with Hartog, four Dissenters also gave evidence before the committee, one of whom was also a Senior Wrangler who had been denied a fellowship.

Adolf Neubauer.

Sadly, Hartog did not become a fellow. Three days after the bill received the royal assent on 16 June 1871 he died of smallpox. However, other Jews soon profited from the legislation. In 1873 Adolf Neubauer who had been responsible since 1868 for cataloguing the Hebrew manuscripts in the Bodleian Library now became eligible for an MA which was awarded in 1873, and after a long wait he was elected an honorary Fellow of Exeter College in 1890.

Samuel Alexander, the first professing Jew to be elected to a fellowship in either Oxford or Cambridge.

Samuel Alexander was the first Jew to become a Fellow at Oxford, when elected to a Fellowship of Lincoln College in 1882. Jews, of course, have continued to benefit from the 1871 Act until today, but arguably Oxford has benefited still more from the many Jewish scholars, heads of house, and donors who have contributed to the University’s life and elite status.

Susan Doran, Professor of Early Modern British History at the University of Oxford and Senior Research Fellow at Jesus College and St Benet’s Hall.