The Enigma of Arrival: V.S. Naipaul in Oxford

The literary career of V.S. Naipaul (1932-2018) was a distinguished one, even among the pantheon of Oxford-educated writers. It was also unusual. Naipaul’s grandparents had been indentured labourers, brought to Trinidad from India to cut sugar cane. He won one of two ‘Island Scholarships’ after years of furious cramming and, instead of the familiar routes of law or medicine, chose to come to University College to read English Literature. That his name is not associated with Oxford – in the manner of Tolkien or Waugh – is probably because he never wrote about his time here. His highly autobiographical works speak in detail about his life in Trinidad before he came to Oxford, about his journey to England and the expectations he carried, and about his life in London after he left university. But the Oxford years themselves – 1950-1954 – are almost never referred to, and then obliquely and guardedly. What we know about his time here comes mainly from the letters he wrote to his family back in Trinidad.

Children attend a Mission school near Chaguanas, Trinidad: the birthplace of V.S. Naipaul. Photograph taken in 1949.

Naipaul’s parents had grown up in observant Hindu communities, in which Bhojpuri was the first language. The excitement they felt when their son went to Oxford is evident in their letters. ‘Write me weekly of the men you meet; tell me what you talked; how they talked’, his father urged him. Vidia’s early letters home are schoolboyish, naïve, and, slightly patronising: ‘You’ve got to know that Oxford is a collection of more than twenty colleges. You hardly can get to know all the people you want. If you want to meet people outside your group in the college, you’ve got to take part in many activities. And if you take part in many activities, you can go out every night’. But quickly the enthusiasm is lost, and the stream of letters, from Vidia’s end, runs dry.

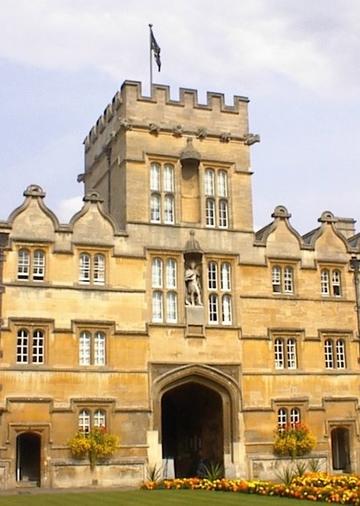

The Main Quad tower, University College, Oxford.

Before coming to university, Naipaul had never left Trinidad. Coming to Oxford, he clearly was expecting to arrive, at last, at the ‘centre’: the enlightened, dynamic republic of letters that his colonial education had taught him to expect and trained him to aspire towards. In fact, he found in Oxford coldness and racial alienation. ‘I have made no friends so far’ he writes. ‘Something, it seems, is wrong with me.’ He was told to ‘keep out’ of the offices of the Isis, because, he believed, he was a foreigner. ‘A feeling of emptiness is nearly always upon me,’ he tells his sister. ‘I feel myself struggling in a […] tunnel blocked up at both ends’.

The Lion House, Chagunas. Immortalised as 'Hanuman House' in V.S. Naipaul's novel, A House for Mr. Biswas.

If there is a single abiding motif throughout Naipaul’s work, it is the false paradise: the painful realisation that the panacea – religious, geographical, historical – in which one had invested was always illusory or remains always just out of reach. The famous house in A House for Mr Biswas purchased by the protagonist after a lifetime of effort turns out to be jerry-built, overpriced, and irretrievably mortgaged; Naipaul returned to his ancestral India in 1962 to find the country at war and himself an alien; and following the revolution in Trinidad in 1970 he wrote his darkest and most violent novels about colonial schizophrenia and the broken promises of independence. But the disappointment of his arrival in Oxford seems to have been in some way foundational.

The Colonial Port of Spain, Trinidad, where V.S. Naipaul grew up. Taken circa 1915.

One winter, after a period of relative silence, his letters suddenly became frequent and lengthy. Alone and on the eve of Christmas, he wrote a long, melancholy letter, describing the wonders and humiliations of his first months; the details of boarding house life, and the magical appearance of ‘his first snow’: ‘A Cow and Gate tin of it weighs less than a pound’! There is a febrile edge to the letter, the beginning of a nervous breakdown that led to a suicide attempt two years later. His father sent him a book by an American psychologist, Outwitting Our Nerves. He was told by a psychologist at Oxford that he was ‘racially insecure’. Such insecurity as he possessed bequeathed him not just his subject matter, but his obsessive attention to linguistic and formal control. ‘No one cares for your tragedy until you can sing about it’ he wrote. ‘I want to come top of my group. I’ve got to show these people that I can beat them at their own language’.

One oblique way Naipaul does talk about his time in Oxford is at the end of his first great novel, A House for Mr Biswas. Anand, standing in for Vidia, has left his dying father, Mr Biswas, to go and study at a foreign university:

Anand’s letters, at first rare, became more and more frequent. They were gloomy, self-pitying; they were tinged with a hysteria which Mr Biswas immediately understood. He wrote Anand long, humorous letters; he wrote about the garden; he gave religious advice; at great expense he sent by air mail a book called Outwitting Our Nerves by two American women psychologists. Anand’s letters grew rare again. There was nothing Mr. Biswas could do but wait.

The poignancy of this passage, and of similar passages in the correspondence – ‘Dear Vido – I think you defaulted a week in writing?’ – will speak to many parents and carers, and to anyone who has been homesick.

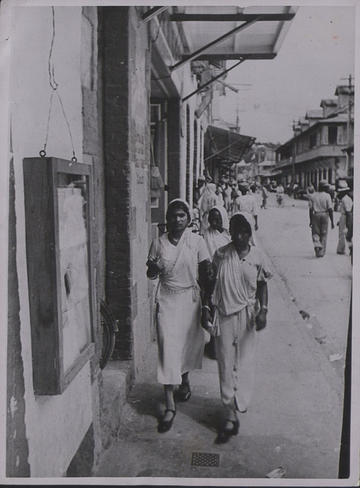

Shoppers in the Colonial Port of Spain, Trinidad. 1945.

As we mark the 150th anniversary of the Tests Act, and the widening of access that it helped inaugurate, experiences like that of Naipaul are important. They tell us that the challenge of broadening the university community does not end at the point when a new group of students are admitted. It also requires attending to the experience of students when they get here. Recently, the University has begun to speak of ‘Inreach’ as well as ‘Outreach’: programmes which attempt to make the whole university community more inclusive, welcoming, and broad-minded. Significant steps are made each year to make our spaces more hospitable and to reflect a broader range of experience in our curricula. Still today, however, there will be students like Naipaul who do not experience Oxford as an arcadia. It is important that we recognize this and learn from their experiences.

William Ghosh, Career Development Fellow in Victorian and Modern Literature at Jesus College, Oxford.