Introduction: Opening Oxford 1871-

Universities, it is said, are places where anything can be debated freely, where freedom of thought should be the rule. This is a very recent idea. For most of their existence universities have done something utterly different. They have sought to stamp out heretical, seditious, and dangerous notions. It is for that reason that books were burnt in the quadrangle of the Bodleian and that radicals such as the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley were expelled from Oxford for expressing subversive views.

Encaenia at the University of Oxford, 1899. (Women were still excluded)

It is for that reason, too, that universities worked hard to prevent the potentially problematic from joining their institution. The Reformation, Protestant and Catholic alike, only intensified this trend as the state expelled and even executed university members for their thoughts and beliefs. In 1581, under Queen Elizabeth I, Oxford ruled that no individual could formally enrol – or ‘matriculate’ – without swearing an oath to the monarch and the Church. Positions within Oxford – whether fellowships in the colleges or professorships within the University – also required similar forms of assent. Far stricter than Cambridge’s restrictions, and those in Ireland and Scotland, this ruling made Oxford the most exclusive university in the British Isles.

The goal was to create a safe space for Protestant orthodoxy. After the restoration of the monarchy in 1660, the effect was even more restrictive than that, with non-conformists expelled and Oxford turned into a narrowly Anglican institution. Attempts to relax the rules were made, but they all failed, and the ongoing orthodoxy of Oxford is still memorialized in a variety of places. The fierce injunction “No Peel!” on a door in Christ Church recalls debates about abolishing anti-Catholic laws in the 1820s. The Peel in question was Sir Robert Peel, an alumnus of Christ Church, MP for Oxford University, once a fierce anti-Catholic and latterly a reformer. His constituents’ views on this U-turn are still vividly apparent. Nearly twenty years later, the Martyrs’ Memorial in St Giles, featuring the evangelical bishops Latimer, Ridley, and Cranmer, was a still more public expression of this mood. Its inscription overtly targeting the Church of Rome was at once a tacit rebuke to the so-called Oxford or Tractarian Movement and its leaders – John Newman, John Keble, and Edward Pusey.

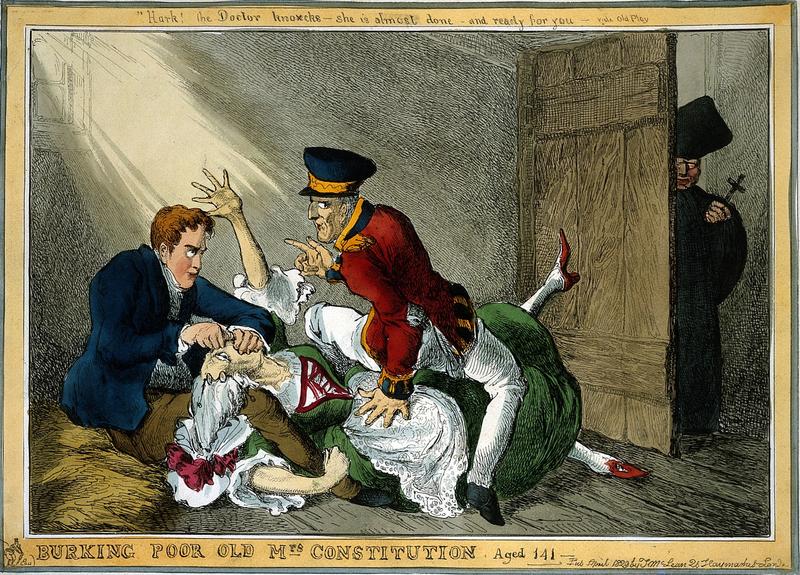

'Burking poor old Mrs Constitution. Aged 141', coloured etching by W. Heath 1829. This satirical cartoon objecting to Catholic Emancipation in 1829 satirises Sir Robert Peel on the left and the Duke of Wellington on the right by showing them dismembering the British constitution, while a Catholic priest lurks behind the door ready to enter. 'Burking' is a reference to the body snatchers Burke and Hare, and possibly to Edmund Burke who had written in defence of the constitution.

Outside Oxford, however, pressure was growing. Inside it, too, a new generation increasingly recognized how distant the University was becoming from society. The rescinding of many political restrictions on Non-Conformists and Roman Catholics in the 1820s; the removal of the bar on Jews sitting in parliament in 1858; the rising number of freethinkers, atheists, and agnostics in public life: all of this made universities seem reactionary and anomalous.

In 1854, the requirement to subscribe to the Church of England at both matriculation and graduation was removed – except for students of Theology. But many colleges retained their barriers – and most jobs remained closed to non-Anglicans. It was not until 16 June 1871 that an act of parliament finally opened the University of Oxford – and Cambridge and Durham – to students and staff of all faiths and none. The Universities Tests Act was intended to ensure that ‘the benefits’ of university education ‘should be rendered freely accessible to the nation’.

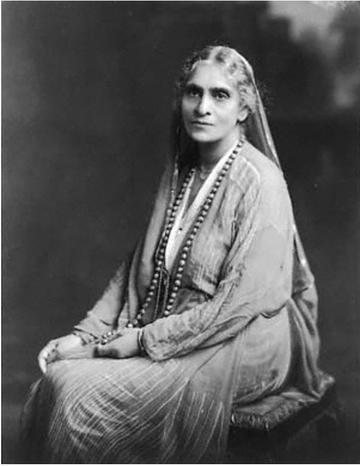

Cornelia Sorabji (1866-1954) who joined Somerville in 1889 and was the first woman and first Indian to read for the BCL in Oxford. Sorabji would not have been able to attend Oxford on account of her faith.

The Tests Act was an incomplete piece of legislation. Many colleges remained only nominally open to a wider range of people. Most, of course, did not open to women until a century later. But the change it heralded was hugely consequential. New colleges were founded, or moved to Oxford, for these new students: Mansfield for Congregationalists and Harris Manchester for Unitarians; Regent’s Park for Baptists; and a succession of Roman Catholic foundations. This reform encouraged people to imagine other sorts of change, with Somerville founded as a non-denominational women’s college and a non-collegiate foundation established which would later enable the creation of explicitly secular colleges such as St Catherine’s, Linacre, and Wolfson.

Ernst Chain, Jewish Nobel Prize winner for his work on penicillin and lecturer at Oxford, in his lab.

Within the wider university, too, brilliant scholars who would have once been excluded were enabled to attend. The Act of 1871 opened the university to the world. It is no coincidence that the decades afterwards saw the arrival of Muslims, Jews, and Hindus, and students from other world faiths to the University and the town. The first Jewish fellow of any Oxbridge college was elected in 1882 and would be followed by a succession of important scholars who would otherwise have been excluded: Ernst Chain, who received the Nobel Prize for his work on penicillin; Dorothy Hodgkin, who received it for her work in chemical crystallography; and others. The Rhodes Scholarships could not have happened without this reform. Oxford’s cityscape was changed, as new buildings were erected that reflected this diversity and old ones repurposed. That today, Oxford Chancellor, Lord Patten, and Vice Chancellor, Professor Louise Richardson are both from Roman Catholic backgrounds would have been unthinkable a century ago. It is only possible because of the Universities Tests Act of 1871.

Here, we will mark the 150th anniversary of that reform with specially commissioned blogs, historical investigation, and personal reflections. We will also host a series of events – from concerts to conversations – to mark the momentous change the Tests Act precipitated. But this anniversary is an opportune moment to think hard about the future as well as the past. We hope to encourage debate about the ways in which the University can open up still further. 1871 began the process of opening Oxford. It is an unfinished story.

More from the Blog

Follow us on Twitter here.