Indians at Oxford

Calls for the repeal of the Universities Tests Act in the nineteenth century were made in a period when religions other than Christianity rarely impinged on the nation’s consciousness. Victorian Britain had a small number of Jews, one of whom (baptised) had even made it to the office of Prime Minister, but it lacked any significant numbers of people of other religions. Even though Britain had recently acquired an Empire, full of different faiths, the modern preoccupation with respecting different religions simply did not arise. The impetus for repealing the Tests Acts came from frustration about missing out on talent from those of other Christian denominations, rather than from any interest in other faiths. For most Christians, other faiths were simply wrong. Their followers had not yet ‘seen the light’ and needed to be persuaded to accept the truth of the Christian gospels.

Proselytizing zeal had its impact on the University of Oxford. In 1832 an old soldier of the East India Company by the name of Lieutenant Colonel Joseph Boden bequeathed to the University the funds to establish a Professorship of Sanskrit. Sanskrit, the classical, liturgical language of several Indian faiths, amongst them Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism, was seen as the key to unlock the secrets of Indian thought and belief. The Professorship of Sanskrit was not founded in a spirit of cultural exchange, however, but rather with the strategic goal of cultural domination. It was expressly designed to assist in ‘the conversion of the Natives of India to the Christian Religion’.

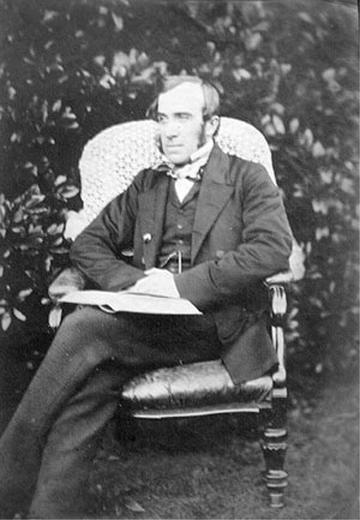

Monier Monier-Williams (1819–1899). Elected Boden Professor of Sanskrit in 1860.

Indeed, the religious (and national) identities of the candidates rather than their competence in Sanskrit determined the outcome of the momentous battle in 1860 for the post of Boden Professor of Sanskrit. It goes without saying that neither candidate espoused any of the religions in which Sanskrit figured. Of the two men standing for the post, Max Müller was handicapped by his nationality (German) and liberal tendencies, whilst Monier Monier-Williams, born in Bombay, was a safe pair of devout evangelical Anglican hands. So, Monier-Williams it was, for the next 39 years. At his inaugural lecture in 1861, he commented specifically on the missionary goal of his new office:

"A great Eastern empire has been entrusted to our rule, not to be the theatre of political experiments, nor yet for the sole purpose of extending our commerce, flattering our pride, or increasing our prestige, but that a benighted population may be enlightened, and every man, woman, and child… hear the glad tidings of the Gospel."

Interestingly, when Benjamin Jowett secured the Boden Professorship of Sanskrit for Balliol in 1882, all mention of the conversion of the ‘benighted’ Indians was quietly dropped from its description. Indeed, Jowett had some genuine interest in India for its own sake and was particularly welcoming of Indians to his College in the years that followed.

Haileybury College, training college for the Indian Civil Service (ICS).

Meanwhile, Monier-Williams had another project in mind. Following the demise of Haileybury College, training college for the Indian Civil Service (ICS), where he had previously both studied and taught, he felt that a place of study should be available for those preparing for the ICS exams and for Indian students. He proposed to the University the foundation of an Indian Institute. His plans were ambitious and included study rooms, a reading-room with Indian newspapers and periodicals, a library, and a museum. Jowett offered a place at Balliol to every man who passed the ICS exams and also temporarily stored the books collected for the Institute. Monier-Williams set off to raise funds in India.

The former home of the Indian Institute, Oxford.

The supreme irony and breath-taking arrogance involved in fundraising among Indians whose religious heritage Monier-Williams aimed to supplant appears not to have occurred to anyone at the time. From the Victorian-Christian perspective, Monier-Williams was engaged in an act of supreme generosity (saving the souls of Indians). Even so, many Indians later complained that the money they had donated had been spent on ‘bricks and stuffed animals’ instead of helping Indian students.

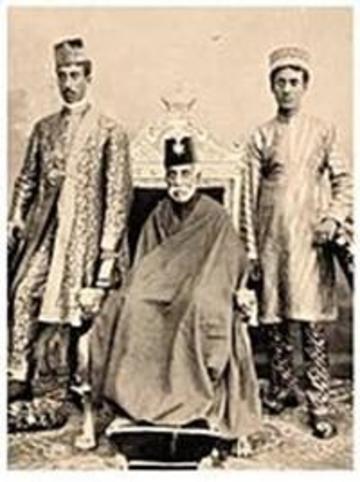

Nonetheless, the British managed to persuade many a Maharaja of the attractive superiority of their culture and induce him to part with not only his money but his sons, who were to be sent overseas to such esteemed institutions as Eton and Oxford. One such was Sir Bhagvat Sinhjee, Thakur of Gondal, who donated £1,400 to purchase the site for the Indian Institute from Merton College in 1896 and whose son Bhojirajsingh studied Engineering at Balliol. Another was Hassan Ali Mirza, Nawab Bahadur of Murshidabad, son of the last Nawab of Bengal, whose sons Wasif Ali Mirza Khan and Nasir Ali Mirza Bahdur came to Trinity in the early 1890s.

The two sons of Hassan Ali Mirza (middle). Wasif Ali Mirza Khan (left) with his younger brother Nasir Ali Mirza Bahdur (right).

With the religious tests removed, increasing (though small) numbers of Indians started to come to Oxford, particularly Balliol thanks to Jowett’s hospitable attitude. They were now free to join the University without denying their religion, be it Hindu, Muslim, Sikh, Jain, or Buddhist. Not all agreed to nod respectfully to the British Empire, however. Shyamji Krishna Varma, a noted Sanskrit scholar, became a revolutionary and founded the India Home Rule Society in London in 1905 before fleeing to France. However, others were courageous in the defence of the motherland, notably Hardit Singh Malik, the first Indian pilot in the Royal Flying Corps in WWI, later the first Indian High Commissioner to Canada and a first-class cricketer. Cricket certainly features amongst Indian alumni, which include the Pataudi dynasty, captains of the India national cricket team for generations, beginning with Nawab Iftikar Ali Khan Pataudi and his son Mansoor Ali Khan (‘Tiger’) Pataudi.

Hardit Singh Malik. Balliol Cricket Past & Present 1921. By kind permission of the Master and Fellows of Balliol College.

The first Indian man to hold a Chair at Oxford was Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan, who became the first Spalding Professor of Eastern Religion and Ethics in 1936. In 1962 he served as the second President of India. His son, Sarvepalli Gopal won the Curzon Prize at Balliol as an undergraduate and gained a DPhil researching the viceroyalty of Lord Ripon in 1951. It was 2007 before the first Indian woman, Aditi Lahiri, obtained a Chair (in Linguistics) at Oxford. Meanwhile, the Presidents of Pakistan, Liaquat Ali Khan and Imran Khan, studied at Exeter and Keble Colleges respectively and India’s first Sikh Prime Minister, Manmohan Singh, gained his DPhil at Nuffield. Nobel Laureate Amartya Sen and author Vikram Seth are also Oxford alumni.

Manmohan Singh with the then Chancellor of the University of Oxford upon receiving his honorary Doctor of Civil Law degree in July 2005. He had previously graduated with a DPhil in Economics from the University in 1962.

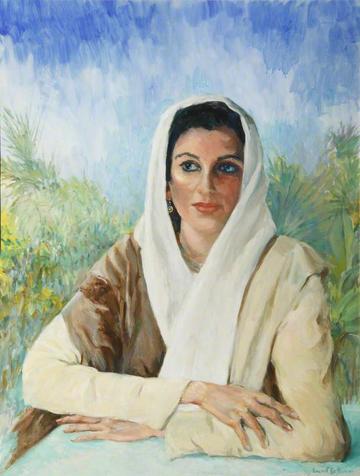

Intriguingly, several early Indian students were women. Somerville alumnae include the two daughters of Duleep Singh, last Maharajah of the Sikh Empire in the Punjab and Maharani Bamba, who later became suffragettes; Cornelia Sorabji, a regular dinner guest at Jowett’s table became the first woman to study law in Oxford and the first female reader allowed in All Soul’s library; Vijaya Lakshmi Nehru Pandit, the aunt of Indira Gandhi, who in 1937 became India’s first woman cabinet minister and later ambassador for newly independent India in 1947. Indira Gandhi herself followed her aunt to Somerville. Benazir Bhutto began a tradition of Pakistani women at Oxford (LMH) which has continued to our own times with Malala Yousafzai.

Portrait of Benazir Bhutto held at Lady Margaret Hall, University of Oxford.

The Indian Institute was ambitious, but ultimately failed through lack of leadership and funds, complicated by two world wars and the collapse of the Empire it had hoped to support. Nonetheless, its building remains at the end of Broad Street and still proclaims a special relationship between Oxford and India. On top is the beautiful gold weathervane (centre image below) in the shape of an elephant with howdah and mahout, the Indian warrior-gods below (left), and at the bottom, the trio of Indian animals (right), the elephant, the tiger, and the bull with downturned horns. And the library still remains, not in its original building but in the Weston Library, which is the greatest Indological library in England.

Indian cultural details as represented on the corner cupola of the former Indian Institute.

The influx of Indians and later men and women of the successor states was an unintended consequence of the Universities Tests Act’s abolition of the Religious Test, but the Act certainly started a process, still ongoing, of diversification within the University of Oxford and increased understanding and respect for the huge variety of the world’s religions and cultures. It finally opened the door to people of all faiths and none.

Victoria Bentata Azaz, MA (Oxon), Green Badge Oxford Tour Guide.