'Football of Church and State': The Irish University Question, 1845-1908

In 1904 an exasperated Catholic student described the university question as ‘the oldest of all living Irish movements ... a sort of political Pompeii’. The longevity of the question might have been exaggerated, but the intensity of the seemingly relentless debate was not. The ‘university question’, as it came to be known, was the general term for the problem of establishing a university or a university college which was acceptable to representatives of the Irish churches and successive British governments in nineteenth and early twentieth century Ireland. The Catholic hierarchy demanded equality for Catholics with their Protestant counterparts and a ‘catholic atmosphere’ in any institution they would support. Representatives of the Protestant churches, particularly the Church of Ireland, sought to protect their own interests, while tacitly extending higher educational opportunities to Catholics. Consecutive British governments attempted to balance a number of disparate claims, while satisfying the demands of MPs, who were increasingly hostile to state funding of denominational education.

The Lanyon Building, Queen's University Belfast.

The establishment in 1845 of the Queen’s Colleges in Belfast, Cork and Galway was the first of a number of initiatives which aimed to provide accessible and good-quality university education to Irish students, regardless of creed. Before their foundation only Trinity College, sole constituent college of the University of Dublin, provided any sort of university education in Ireland, though Catholics with means could attend universities abroad or go to Maynooth College if they hoped to embark on a clerical career. Founded in 1591, Trinity was a Protestant institution, upholding the teaching of the Established Church and educating many of its clergymen and theologians. The Catholic Relief Act (1793) allowed some Catholics and Dissenters to enrol and obtain degrees, but professorships and fellowships remained closed to them. As Catholics made up around 75% of the Irish population (and Dissenters around 10%) by 1800, Trinity clearly served only a small minority of the country and its standing as a bastion of the Protestant ascendency came under increasing scrutiny.

The front gate of Trinity College Dublin.

The Queen’s Colleges, linked to form the Queen’s University in 1850, offered low fees and good scholarships. They were secular, but provision was made for the pastoral care and religious instruction of students of various denominations. Some Catholics welcomed this initiative, believing that the co-education of Catholics and Protestants would promote mutual understanding and good relations. But the Catholic hierarchy condemned the Colleges absolutely, barred priests from taking up posts in them and instructed lay Catholics to shun them. This opposition to ‘mixed education’ and insistence on a ‘Catholic atmosphere’ contributed to the establishment in 1854 in Dublin of the Catholic University under the rectorship of John Henry Newman, who had recently converted to Roman Catholicism. The University struggled without a charter or an endowment, and never became the lively and successful institution that had been envisaged.

Another attempt at a settlement followed in 1879 when the University Education (Ireland) Act made way for the dissolution of the Queen’s University, and the establishment of the Royal University of Ireland, an examining body only. The Royal had the power to grant degrees to anybody who passed its examinations; where or by whom students were educated made no difference, except in the case of medical students. It also offered fellowships to a range of schools and colleges which prepared students for the Royal’s exams. The Royal was acceptable to most parties, partly because while it did not support denominational education, it did allow, albeit indirectly, for religious instruction and funding for denominational education in the many schools and colleges which prepared students for its examinations.

'The nine graces', 1883. The first women to graduate from the Royal University.

The Royal University satisfied no party completely, but it was progressive in many respects. It allowed for the education of students of all denominations to whom all prizes and scholarships were open, and it provided for the education of women on a scale unmatched by other systems or institutions in the UK, except perhaps London University on which the Royal University was partly modelled. Women university students faced all sorts of obstacles, but legally at least, they had full educational equality with male students.

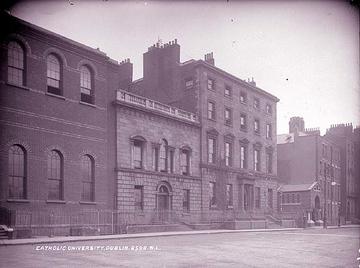

The Catholic University at St. Stephen's Green, Dublin. Reconstituted as University College, Dublin in 1882.

The old Catholic University was reconstituted as University College, Dublin in 1882. It regularly received half the Royal’s salaried fellowships, allowing it to build a lively collegiate and academic centre in Dublin and a form of a Catholic university college. Nonetheless, by the turn of the twentieth century, most Catholic educationalists were utterly frustrated: the Royal University continued to function as a purely examining body, denominational education was not directly funded, and an endowed institution suitable for Catholics, had not been created. At the same time, the prestigious and well-endowed Trinity continued to serve primarily a small minority of Anglicans and to guard its privileges. In 1873, the Dublin University Tests Act, removed the religious tests for all offices and prizes in the University, apart from in the Divinity School. This did not soften the Catholic hierarchy’s view of Trinity as unsuitable and even dangerous for Catholic students. The Church’s disapproval was not binding on individual students, but priests were compelled to discourage prospective students; this ‘discouragement’ was often known as a ‘ban’. Despite their disapproval, the number of Catholics at Trinity changed very little between 1859-1890, making up to an average of between six and ten percent of entrants in each year. It increased rapidly over the twentieth century.

Statement of Chief Grievances of Irish Catholics in the Matter of Education, Primary, Intermediate, and University. By the Archbishop of Dublin, William J. Walsh. 1890.

Despite many more attempts at a settlement, including the establishment of a Catholic College within the University of Dublin, it was only when the hierarchy finally conceded that a Catholic University would not be funded and that Trinity would not be interfered with, that a settlement seemed likely. The Irish Universities Bill of 1908 dissolved the Royal University and allowed for the establishment of two new universities: the National University of Ireland, encompassing the old Queen’s Colleges in Galway and Cork and a transformed and endowed University College Dublin; and Queen’s University Belfast. The settlement finally placated most interested parties, but it was hardly greeted with enthusiasm.

The Irish University Question. By the Archbishop of Dublin, William J. Walsh. 1897.

In common with every previous university scheme, the National University’s religious complexion proved to be the settlement’s most contentious aspect. The University’s non-denominational status attracted criticism and there was further debate about the status of women in the new institution. But despite this and the long history of abandoned schemes and wrecked plans which preceded them, both universities developed within their own contexts and communities to grow into prestigious and successful national institutions, open to students of both sexes and all denominations and none.

Senia Paseta, Professor of Modern History, St Hugh’s College.