Christ Church and the 1871 Universities Tests Act

It is astonishing that the records of a college with an attached Anglican cathedral say almost nothing about the lifting of religious ‘tests’ for many undergraduates in 1854 and then most dons in 1871. Or is it? Dean Gaisford, Head of House, in post until the summer of 1855, was adamantly against reform of either Church or University. Reforms to the examination system some fifty years before were anathema to him, and he was determined to retain the distinctions between poorer and richer members of college, and refused to allow servitors (the lowest rank of undergraduate who undertook menial tasks in exchange for tuition) to become Students (stipendiary members). The idea that the University should accept men who were non-Anglican probably never crossed his mind.

Thomas Gaisford (1779-1855).

However, in spite of Gaisford’s refusal to answer any of the questions sent out by the Royal Commission of 1850, reform was inevitable. The Dean must have felt that the prime minister, William Gladstone, one of the drivers of University reform, was stabbing his alma mater in the back. The 1854 Act – aided and abetted by the 1840 Cathedrals Act, which reformed the other part of Christ Church - began the gradual demolition of three hundred years of Dean and Chapter control.

Henry Liddell (1811-1898).

Perhaps to the relief of the University Commission, whose task it was to put the 1854 Act into effect, Gaisford died in June 1855 to be replaced as Dean by one of the Commissioners, Henry Liddell. He had diligently attended all but one of the 87 meetings. Liddell was not an out-and-out reformer but he understood that the winds of change were upon Christ Church, and was sympathetic to the proposal that Students would not have to be in holy orders. That it was Liddell who was appointed Dean may be another explanation for there being no records here, particularly concerning the 1871 Act; his discussions about Christ Church and its response to the proposals were probably conducted beyond the walls of the college and cathedral.

Exterior of Christ Church Cathedral.

A third reason for the apparent lack of debate may be that Christ Church was, between the mid-1850s to the 1870s, suffering a constitutional crisis of its own which focussed on matters beyond those of the 1854 and 1871 Acts: a struggle for control between the Students and the Cathedral chapter.

Edward Bouverie Pusey preaching in Christ Church.

Even so, while money and the dilution of governance seem to have been the biggest hurdles for the reform of Christ Church, it is still strange that a college so entirely governed by clergymen should barely have noticed or commented upon the proposal that the University should admit Non-conformists. Christ Church had used (and continued to use) its dual nature to exempt itself from any legislation relating to colleges or cathedrals of which it did not approve, but these two reforming Acts anticipated this and specifically declared that Christ Church was to be considered a college. Opening up the University to undergraduates of all religions and beliefs and none, seems to have been adopted without so much as a murmur, although the 1858 Ordinances expected all those with MAs and below to attend Divine Worship in the cathedral; a significant departure from the University’s decree that Anglican worship should be merely available for all, rather than compulsory. There were those who were vehemently against such changes, like Edward Bouverie Pusey and Liddon. Pusey had washed his hands of the 1858 Ordinances: ‘I have done what I could towards retaining the old Christ Church’, he said in a letter to the Dean, ‘I shall not keep up an ineffectual struggle’. Liddell replied cheerfully that ‘Old Christ Church is … in a state of decay and must (if not restored) fall into decrepitude. But I … accept the responsibility’.

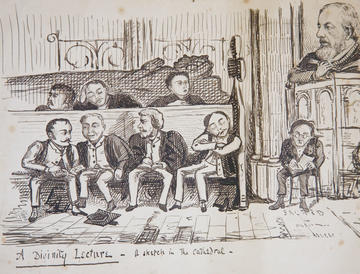

Prints SOC A (lecture).

While Liddell had batted through the 1854 Act before he became Dean, by 1870 he was Vice-Chancellor of the University and in an even stronger position to influence the debates around University Tests and the proposed Act of Parliament designed to tidy up issues still outstanding from 1854, not least the opening up of fellowships and other senior posts to non-Anglicans. This time it would appear that the new Governing Body – created in 1867 - dragged its feet. They had banked on support from old Housemen in Parliament not least William Gladstone but he now considered himself free of Oxford, having taken a seat in Lancashire, far away from the machinations of the University, and declared himself to be ‘unmuzzled’. Lord Salisbury was an ally, appointed as University Chancellor in 1869, and against the de-Anglicisation of the University. Christ Church felt it would be safe from further reforms. But their complacency was short-lived; in 1880, the Liberals swept back into power and any notion that denominational privilege was acceptable was shattered. In 1882, the third iteration of Christ Church’s new statutes (only ratified in 1867) required only three Students (Fellows) to be orders. Governing Body slowly became increasingly secular or non-conformist, catching up with its undergraduates whose numbers included or soon would include, among others, Scottish Presbyterians, Greek Orthodox, Congregationalists, Parsees, Methodists, Buddhists, Jews, and Catholics.

Judith Curthoys, Archivist, Christ Church, Oxford.

More from the Blog

Follow us on Twitter here.