Changing Oxford Religion

Much has been written on the changing nature of Oxford University after the reforms of 1854 which culminated in the abolition of the religious tests in 1871. Yet, what has seldom been noted is the profound effect that University reform had on Oxford parish life. In 1800 not a single Church of England church in the city of Oxford had a resident parish priest: they were served by resident fellows of colleges who supplemented their fellowships with the meagre income of the parishes in return for a modest amount of pastoral work. These clergy nearly always moved on after a few years after marrying and taking a better-endowed parish elsewhere. All the Oxford parishes were remarkably poor and did not offer anything like the income required to support a clergyman and his family: the University Church, for instance, yielded a mere £37 per year, which meant that its most famous vicar, John Henry Newman, had no choice but to retain his fellowship at Oriel. Some parishes relied on junior fellows to take Sunday services, and sometimes pastoral work was undertaken only during the university vacations. Effectively, the parishes existed solely for the townspeople – undergraduates and fellows were presumed to have plenty enough religion in their colleges. This situation remained much the same through to the 1840s: there were under 20 clergy ministering in the parishes, and nearly all of these were very much part-time. By 1854, however, the number had increased to well over forty – and continued to expand through the century, faster than the population of the city. Even though stipends increased slightly they were never enough to support the needs of married clergy. By the end of the century all the parish priests were resident in their parishes and functioning as full-time professionals, often with a team of curates. There were also usually married men of private means devoted to the task of evangelism, prepared to sacrifice income for mission and for influence on impressionable minds. They also stayed for much longer in their parishes.

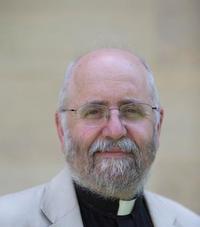

The Rev. Canon Christopher, rector of St. Aldate's Church, Oxford.

After 1854 and even more so after 1871, with the University apparently less interested in the spiritual education of its students, the Church of England – along with the other denominations – began to pay far more attention to the welfare of their souls: parish churches were not just for the townspeople. For instance, the long-serving Rector of St Aldate’s A.M.W. Christopher wrote in 1889 that Oxford students were no longer going to ‘a home of religious training and influence, as aforetime was the case when a college was true to its idea’. Instead, they were going out into a world that required what he called an ‘aggressive’ religion to maintain the case of ‘faith and goodness in the open field’. Four years later he set up the Oxford Pastorate as a source of spiritual support for students to ‘take up the spiritual side of the ideal tutor’s work’ (and to ensure that his Evangelical ideas were not lost in what was perceived to be the increasingly hostile university environment and that they did not fall into the sway of the Anglo-Catholic Pusey House). Pembroke College was happy to grant its patronage of St Aldate’s to the Charles Simeon Trust in 1859 which ensured an Evangelical succession; and a few years later the Evangelical Oxford Trust took control of four parishes including St Ebbe’s and St Clement’s.

Church of St. Philip and St. James, c. 1870.

The Colleges, especially St John’s and Christ Church, were also active in expanding ministry in their parishes with resident clergy and new church buildings – as with the building of churches for the new suburbs in North Oxford (St Philip and James) and Osney (St Frideswide’s), usually with a much more ritualist flavour. Others with even more exotic Anglo-Catholic churchmanship were funded by wealthy individuals and given to the Anglo-Catholic Keble College (St Barnabas, Jericho).

St. Barnabas Church, Jericho, Oxford, c. 1880.

By the end of the century students were flocking to parish churches where they could experience something a little more colourful and enthusiastic than the often dry-as-dust worship of their college chapels. Alongside this revival was an equally important development of pastoral work in poorer parts of the city and efforts to draw in the working classes through mission halls, as well as new churches in less salubrious areas (as with St Mary and St John on the Cowley Road, or Holy Trinity Church in St Ebbe’s parish). A commentator wrote in 1888: ‘fifty years ago the intellect of Oxford was concentrated on theology: nowadays Oxford is actively interesting itself in the poor and uneducated’. All this meant that the increasing liberalisation of the University led to a vast expansion of religion in Oxford: for the first time there was a proper religious marketplace in which the Church of England more than held its own, boosted as it was by earnest clergy keen to make their mark. The ‘secularisation’ of the University was certainly not accompanied by the secularisation of Oxford or its students.

Mark Chapman, Vice-Principal of Ripon College, Cuddesdon and Professor of the History of Modern Theology.