Anti-popery in Victorian Oxbridge

The Universities Tests Act of 1871 removed all restrictions, tests and disabilities preventing Roman Catholics from studying, taking degrees, and working at England’s universities. As the Act’s preamble declared, it aimed thereby to render these seats of learning ‘freely accessible to the nation’. However, English Roman Catholics hoping to study at both Oxford and Cambridge continued to face considerable obstacles.

Somewhat surprisingly, the greatest of these obstacles came from the Roman Catholic Church itself. A handful of English Catholics had begun attending Oxford and Cambridge following the loosening of laws prohibiting their attendance in the mid-1850s. However, the English Catholic hierarchy was very keen to quash this development, fearing that such attendance would lead to the corruption of young Catholics’ morals and the loss of their faith. The attitude of Bishop Cornthwaite of Beverly, expressed in a circular sent to his clergy in 1867, is emblematic: ‘unless (which is next to impossible) the precautions are such as to remove the imminence of the danger, to pursue a course of studies in these Universities would be grievously sinful in the sight of God’.

Baron Anatole von Hügel (1854–1928), painting by P. Voluzan, 1899-1900 [Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, University of Cambridge].

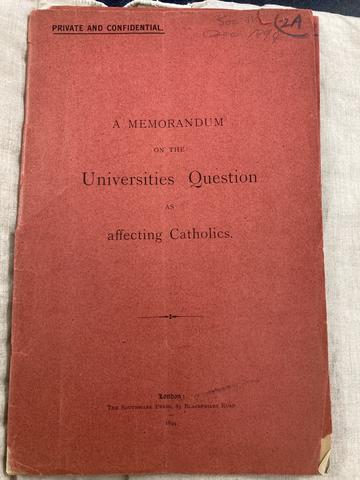

However, despite the intransigence of the English Catholic hierarchy, in the wake of the Tests Act calls started to mount amongst the Catholic laity for a change of policy. One of the most prominent voices for change was Baron Anatole von Hügel, director of the Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology in Cambridge. In 1894, von Hügel organised a petition containing the names of sympathetic priests, religious, leading members of the Catholic aristocracy and former Oxbridge students. It was presented that year to Herbert Vaughan, Cardinal-Archbishop of Westminster, and subsequently circulated in a memorandum addressed to the English hierarchy under the title, A Memorandum on the Universities Question as Affecting Catholics (London, 1894).

A Memorandum on the Universities Question as affecting Catholics (London, 1894) [Cambridge University Library GBR/0265/UA/SOC.IV.2].

The Memorandum set out a persuasive case for change. Catholic attendance at Cambridge and Oxford was presented as an important means not only to boost the careers of lay Catholics, but also thereby to help influence the political, social and intellectual life of the nation. In addressing the hierarchy’s fears about the perversion of young minds, the Memorandum argued that the experiences of those Catholics who had studied at both Cambridge and Oxford over the previous thirty years had shown such fears to be unfounded. Von Hügel provided his own testimony, having ‘seen more than three generations of Catholic undergraduates pass through Cambridge’. Not only had the faith of none of these undergraduates suffered, von Hügel insisted, but ‘their presence in the University has certainly helped to diminish the existing blindness in matters concerning the Church.’

Arguments such as these eventually helped persuade a majority of English Catholic bishops that change was indeed needed. After discussions with the papacy, Cardinal Vaughan and his fellow bishops issued an Instruction to the Parents, Superiors & Directors of Catholic Laymen who Desire to Study in the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge in 1896. This pamphlet explained how ‘the residence of Catholic Laymen at the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge would henceforth be tolerated’ on a number of conditions. These included stipulations that all Catholic residents at the universities attend regular courses of lectures by Catholic professors, ‘in which Philosophy, History, and Religion shall be treated with such amplitude and solidity as to furnish effectual protection against false and erroneous teaching’.

Nevertheless, although it officially sanctioned Catholic attendance at the English Universities, the Instruction was far from a ringing endorsement. In the eyes of both the papacy and the English hierarchy, the establishment of a Catholic university in England remained the most desirable solution to the ‘Universities Question’. The relaxation of the Church’s prohibition on Oxbridge attendance was therefore presented as a temporary stop-gap, and it was at pains to clarify that it was not offering ‘even a general encouragement to all who can afford it to frequent the national Universities. Far from it.’

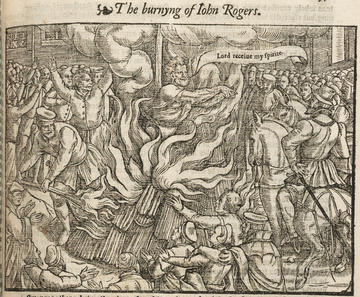

Alongside the attitudes of the Roman Catholic Church, English Catholics attending the universities in the wake of the Tests Act also faced another obstacle: widespread anti-Catholic (or ‘anti-popish’) prejudice amongst the British people. Anti-popery had its origins in the Reformation of the sixteenth century, when successive generations of Protestant reformers had demonised their confessional opponents as tyrannical, devil-worshippers hell-bent on the destruction of the true Church. No printed work was more significant in propagating this image than John Foxe’s Acts and Monuments, first published in 1563, which detailed in meticulous and gory detail the burning of Protestants by Catholics during the brief Catholic revival of Mary I’s reign (1553-1558). Foxe’s work was subsequently reissued in multiple new editions throughout the sixteenth, seventeenth, eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

'The burnyng of John Rogers', from John Foxe, Acts and monuments of these latter and perillous dayes (London, 1563) [Houghton Library, Harvard University, HEW 6.11.1].

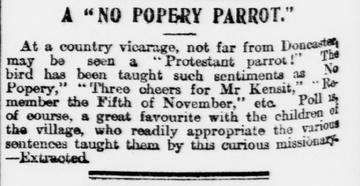

Although much of the legal framework discriminating against English Catholics had been removed by the early nineteenth century, anti-Catholicism remained a ubiquitous cultural force in Victorian Britain. In fact, anti-papal attitudes were given new impetus in 1850 with the papal re-establishment of the Roman Catholic hierarchy in Britain (an act popularly dubbed ‘the Papal Aggression’). Over the remainder of the century, countless newspaper reports can be found detailing instances of popular anti-popery throughout the country. These ranged from violent protests, such as ‘anti-popery riots’ in late 1860s Birmingham, to rather more unexpected manifestations, such as a report from 1899 of a small country vicarage near Doncaster in which a pet parrot had been taught to spout anti-Catholic slurs!

Excerpt from Hull Daily Mail, 26 July 1899 [British Library Newspapers].

The extent to which anti-papalism affected those studying at Oxford and Cambridge in this period is not entirely clear. The 1894 Memorandum discussed above included the testimonies of a number of Jesuit Fathers at Oxford who downplayed the prejudices facing Catholic undergraduates:

During the last twenty years opinions about the Catholic Church have immensely changed in Oxford, and though there is still a hearty dislike of it among Church people, still, among the advanced thinkers in the University, there is a respect growing….

However, it is worth remembering that these individuals had a vested interest in downplaying religious tensions at the university – it was only by presenting Oxford as a safe place for Catholics that they could persuade the hierarchy to relax the prohibition on attendance. In reality, anti-popery appears to have been alive and well at both Oxford and Cambridge, even at the very end of the nineteenth century. Indeed, the extent of anti-Catholic feeling at Cambridge can be seen in the furore surrounding a vote at Senate House in May 1898 regarding proposals (again orchestrated by von Hügel) to recognise St Edmund’s House, a Roman Catholic house of study, as part of the University.

Senate House, University of Cambridge.

In the lead up to the Senate House vote, opponents of the proposal voiced their opinions in the local press. For some, opposition stemmed from a liberal desire to keep Cambridge as free as possible from all sectarian interference (even that of the Church of England). However, others set out more traditional objections: one individual writing in the Cambridge Independent Press on 6 May voiced his concerns in terms eerily redolent of John Foxe’s Acts and Monuments:

the choice is between retaining our National religion, as elaborately reformed in the 16th Century (and by Cambridge divines, observe), and restoring Popery…Liberal politicians can surely have no hesitation in voting for the former of these alternatives. For with religion social life was rescued from misery by the Reformation. Have we freedom? Have we a sound constitution, an admirably-limited monarchy? Trace it all to the Reformation.

The vote itself on 12 May was also disrupted by anti-Catholic outbursts. One newspaper reported that a large group of undergraduates ‘had suspended from one gallery a splendid rubbing from a brass monument with the words “No Popery” inserted at the foot’. Meanwhile, ‘[t]here were loud and continuous cries of “No Popery” whilst the votes were being taken’. In the end, the measure was overwhelmingly rejected. As one of von Hügel’s supporters wrote sadly to his friend in the wake of the defeat,

I am sick and ashamed that the University should have shown itself so intolerant. I have been in the habit of thinking that there was an advance in such matters everywhere, and especially at Cambridge. I thought that we had all of us learnt to respect one another’s beliefs and opinions; that Christians thought more of their agreements and less of their differences, and that agnostics were less aggressive. It is not so, and I am very sore accordingly.

To conclude, therefore, whilst it is right to celebrate the Universities Tests Act as an important milestone in the creation of a more open Oxford and Cambridge, we need always to remember that England’s universities did not become welcoming places for religious minorities overnight. Long after the ink had dried on the 1871 statute, English Roman Catholics continued to grapple with deep-seated antagonisms and intolerances, not only from Protestants and liberals, but also from their own co-religionists.

Frederick Smith, Early Career Fellow in Early Modern British History at Balliol College, Oxford.