Oxford was my first experience of England and English life outside of books, or my school and undergraduate college (both of which had been set up by English colonials). And it was a life-changing experience in the best sense, introducing academic and social worlds I would never have had access to elsewhere. I was fortunate to be at Wolfson, a cosmopolitan, egalitarian, and friendly college and even more fortunate in my DPhil supervisor, Jon Stallworthy. Jon never set deadlines, seldom reminded me that I was at Oxford to complete a degree and not just to visit pubs or go to concerts or dine with friends, or travel. He did, however, direct my work with unerring judgment and good humour and ensured I managed to submit a dissertation in due time. I remember his staunch defence of my application for a US visa to conduct research, and his anger that it was initially refused on grounds he thought were spurious and possibly racist. In retrospect I think he was right and it reminded me that while racism existed there were people like Professor Stallworthy who were willing to stand up for me.

Matriculation Day, 1995.

I was equally fortunate to have friends of all races who were incapable of racism, not because it was politically incorrect, but because they never thought of me as an ‘other’ who had somehow wormed his way into the hallowed portals of Oxford. I suppose Oxford in the mid to late 1990s was more of an elite bubble than it is today but I seldom felt out of place. This is not to deny that I felt visible in ways I would not in India and often called upon to explain Indian culture and its complexities and oddities. I remember being asked about whether I thought the English had done any good in India – the enduring myth of a benevolent empire – and trying to explain that the colonial project is not fundamentally or structurally designed for the good of the colonised. I recall instances where I had to explain that while I was a Hindu I didn’t speak ‘Hindu’ (or Hindi, as my first language). While on the subject of being Hindu, I faced no religious discrimination. My school and college in India had introduced me to church services and I had even sung in choirs in my youth. I especially enjoyed Evensong at various colleges in Oxford and performances of Handel’s ‘Messiah’ around Christmas time. There’s something quite magical about listening to choirs singing in medieval churches, a blend of the religious and the secular that modern-day Oxford offered to someone like me from a different faith tradition.

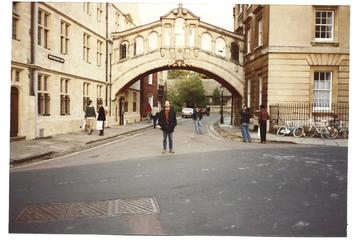

'The Bridge of Sighs', c. 1995. Hertford College, Oxford

The English fascination with curry was a source of great delight, even if curries served in England had little in common with what I ate at home. There was one restaurant on the Cowley Road, Mirch Masala (now sadly defunct), that served fairly authentic Indian food. It was run by a Pakistani married to an Indian, virtually unthinkable in India then and perhaps impossible today. When India beat Pakistan in the 1999 Cricket World Cup (at the same time the two countries were fighting a war in Kargil), I went for a celebratory dinner with some cricket fans to Mirch Masala and we had a wonderful meal and conversation with the Pakistani owner. Only in Oxford would such conversations be possible.

Graduation with a view of the University Parks cricket pitch and pavillion. 22 May 1999.

One final anecdote: Wolfson put a choir together and we were due to perform on a fine day in May. The performance was preceded by a picnic during which I mentioned a concert by Simon and Garfunkle I’d seen on VHS tapes. One of the choristers or perhaps someone sitting in the circle asked, ‘Did you see that in your village?’ In a rare display of presence of mind I replied, ‘Yes, in my village in Calcutta.’ The awkward silence was broken and I was known as the ‘village yokel’ from then on.

Subarno Chattarji (DPhil, American Literature, 1999) Professor in the Department of English, University of Delhi.