The Paradoxes of Reform: Keble and Confessionalism

When Keble opened its doors to its first students in 1870, the year before the removal of the University tests, it was as a college intended only for members of the Church of England, and as its early appeal literature stated, the new foundation would ‘tend to promote the supply of candidates for Holy Orders’. Its confessional integrity was to be maintained by means of an external Council comprised of Anglican leaders; the Warden and Bursar were members, but the Fellows were excluded. Chapel attendance by students was compulsory and it was only in the 1930s that non-Anglican students were admitted at the discretion of the Warden. As late as 1962 nearly three quarters of the student intake declared themselves to be members of the Church of England. In spite of the ambitions of its founders that it be more than a theological college, in its early years it was strongly clerical in ethos. 37.5% of its students were sons of clergy in the 1930s; nearly half were proposing to seek ordination, and at least a third actually did so. The College was able to accumulate an impressive amount of ecclesiastical patronage because of its loyalty to the Anglo-Catholic tradition. ‘Secularisation’ was to be a long drawn out process. The Fellows had to wait until 1952 to become fully self-governing, and the requirement that the Warden be in holy orders was only removed in 1969. The first lay Warden was Christopher Ball appointed in 1980.

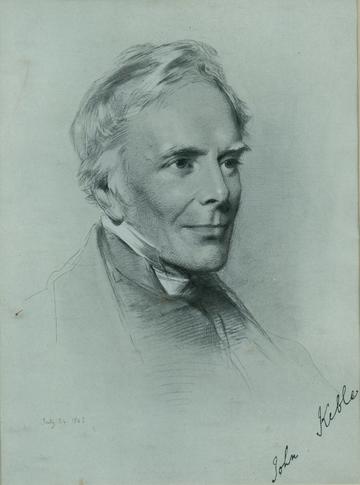

John Keble by George Richmond.

Keble had been founded with the intention of making an Oxford education available to ‘gentlemen wishing to live economically’. The College can be regarded as a legacy of the Oxford Movement, an effort to recover the Catholic heritage of the Church of England. The movement did not oppose all change; indeed, several of its key supporters were leading advocates of what was called ‘University extension’. They included John Keble (1792-1866) himself, and when he died in 1866, a college seemed to be an appropriate memorial. His fame within the Anglosphere was largely down to his collection of poetry, The Christian Year (1827), which went through ninety-five editions in his lifetime. He was obituarised as ‘the sweet singer of our Church, the Poet and the Saint’. But that was to airbrush the more controversial aspects of his career. Stung by the undermining of the Anglican monopoly by recent Catholic Emancipation, and the threat of further attacks on the Church’s position by the reformed parliament, he had preached a key sermon on the theme of National Apostasy in the University Church in April 1833. The occasion of the sermon was further state interference in the Church in Ireland, but Keble broadened the attack, denouncing the abandonment of key Christian principles and calling for a recognition of the Catholic traditions of the Church of England. Among the signs of the ‘apostate mind’ he identified was a spirit of religious indifference, or what we might call toleration. John Keble was thus far more polemically engaged than his later reputation suggests. When the requirements for BAs to subscribe to the tests had been dropped in 1854, the first stage in the dismantling of the Anglican monopoly, Keble was outspoken in his opposition, calling on his supporters ‘to disavow, deprecate, resist it to the very uttermost of our power; and at the same time, to be quietly preparing places of refuge, if God permit, for those who are likely to suffer by it’. These were wild words.

The Chapel of Keble College, Oxford

It is important to realise, however, that many people did not see any incompatibility between the principle of a University open to a variety of religious opinions, and individual colleges which might retain a confessional character. So, some of the key movers behind the repeal, several of them friends and associates of Keble, were supporters of the College project. W.E. Gladstone, a late convert to repeal but under whose first premiership the legislation passed, had stressed to Canon Liddon the urgency of a memorial to Keble on the very day of the funeral, and himself donated £200 to the fund. His niece by marriage, Lavinia Lyttleton was married to the College’s first Warden, Edward Talbot, appointed at the age of just twenty-five; Gladstone was a regular visitor to the Warden’s Lodgings in the College’s early years. Other prominent repealers appear as donors: J D Coleridge who introduced an unsuccessful repeal bill in 1868 gave £50; he had been heavily influenced by the Tractarians as a young man. But the College also received support from the opponents of repeal. Viscount Cranborne (marquess of Salisbury from April 1868), whose opposition in the Lords led to significant amendments to the legislation, donated £250.

The interior of Keble College Chapel.

Keble’s story reminds us that there were different ways of opening the University up: to those of more modest means, as well as to those of different religious persuasions. The complexity of alignments is also evident over the issue of opening up the University to women. The Talbots, Edward and Lavinia, were both enthusiasts for the cause of women’s education, and the meeting to establish Lady Margaret Hall was held in the Lodgings at Keble on 4 June 1878. But after a split among the progressives, LMH was to be an Anglican institution, whereas Somerville was founded on non-sectarian lines.

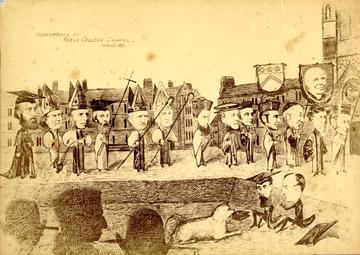

Cartoon on the dedication of the chapel, 1876.

The Chapel continues to dominate the physical impression Keble College makes, and its community is well supported, but in many ways the College today is a very different place from that envisaged by is founders. Since the 1960s the range of subjects has enormously diversified; women were admitted in 1979, and the first female Warden appointed in 1994; the balance of undergraduates and postgraduates has profoundly shifted; and access means something very different from the advocates of nineteenth-century extension. Keble is a much more internationally diverse body; like other colleges it has done much to broaden the social range of its intake, while recognising that there is much more that it needs to do. The College respects its past but seeks to inspire the future.

Ian Archer, Associate Professor in History and Fellow at Keble College, Oxford.

More from the Blog

Follow us on Twitter here.