The Letter of the Law: The University’s Response to The Oxford University Act of 1854

The Act of last year would be a dead letter if all those who entertained conscientious doubts as to the propriety of some of the doctrines… were to be excluded from the University. He… thought it was like compelling a man to wear a cockade in his hat when the object of the law was to abolish the use of cockades altogether.

(Speech by the Lord Chancellor – University of Oxford Petition, House of Lords, 13 August 1855)

The Oxford University Act of 1854 included clauses which explicitly removed the requirements for students of the University to make oaths or subscriptions (including those of a religious nature) on matriculation or when taking the ‘lower’ degrees (BA, BCL, BM, B Mus). How then could there be any cause for the House of Lords to discuss the University’s requirement for undergraduates to make statements regarding their religious views a mere year later? The answer lies in the efforts made by the conservative officers of the University to undermine the intention of the Act.

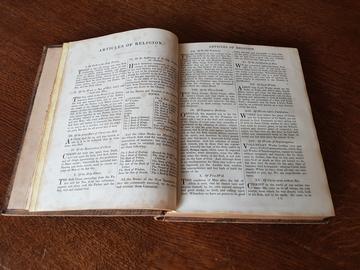

According to University Statute, from 1581 (and further codified in the Laudian Statutes of 1636), all those joining the University over the age of sixteen were required to swear two oaths – to accept the British monarch as supreme authority in all matters, temporal and spiritual (the Oath of Supremacy) and to subscribe their assent to the 39 Articles (the core doctrines of the Church of England). That such oaths had been required is unsurprising given the University and colleges’ close association with the established Church, acting as an Anglican seminary for centuries. Although it was a last-minute addition to the 1854 Act (which was originally intended to force some of the changes recommended by the 1850 Royal Commission on a recalcitrant University), the removal of this requirement nevertheless reflected the atmosphere of reform and growing religious tolerance within the wider nation.

Articles of Religion (1854), Oxford University Archives.

Whilst the spirit of these clauses was clearly to remove any religious requirements from the 'lower' degrees, this ran contrary to the deeply-held beliefs of those who held positions of power within the University. These men, a product of the ecclesiastical University, valued uniformity and conformity to the established Church, and as such, sought to protect these links, minimising the impact of the Act by abiding strictly by the letter of the law.

Clause 44 states it would not be necessary for a student taking one of the lower degrees to ‘make or subscribe any declaration’. Instead, the University authorities made changes to the statutes which instead, offered students a choice. Candidates had to sign one of two books – one which included a subscription to the 39 Articles and one that did not. By making this a choice for the candidate, rather than a requirement to subscribe, the University authorities neatly side-stepped the intent of the law, instead ‘designating’ students as members or non-members of the Church of England and reinforcing the ‘otherness’ of Dissenters.

Until this time, examinations in Theology, including a section on the 39 Articles, had been a compulsory part of the undergraduate curriculum. Instead of abolishing this requirement, or making it optional for all, the University offered a choice. Those who wished to be excused from this part of the examinations had to present a certificate to the proctors from their head of house stating that they wished to be excused on the grounds that they were not a member of the Church of England. Again, the University was technically within the law – it did not require the declaration from the candidate, it simply required proof from the head of house that such a declaration had been made to them. Furthermore, it was required during examinations, not matriculation nor when taking a degree.

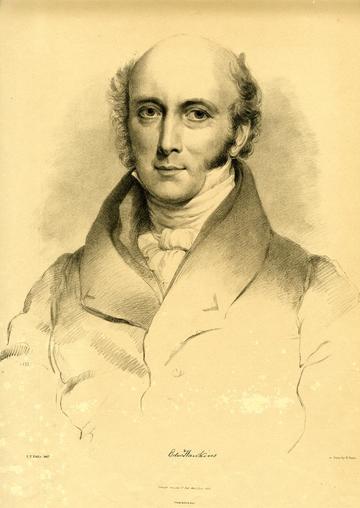

Edward Hawkins, Provost of Oriel, 1789-1882.

The University authorities were so narrowly interpreting the Act that they actually sought legal counsel that they were remaining within the law. These two interpretations of the Act by the University came to wider attention when the Provost of Oriel, Edward Hawkins, interpreted them even more narrowly. In August 1854, Sir Culling Eardley applied for readmission to his college, Oriel. He had previously passed all of his examinations but had not taken his degree because, although identifying as a member of the Church of England, he had reservations about subscribing to the 39 Articles. Hawkins interpreted the combination of the above choices to mean that those who did not identify themselves as extra Ecclesiam Anglicanam must sign the ledger subscribing to the 39 Articles. Disgusted, Eardley submitted a petition to the House of Lords, where all agreed Hawkins’ interpretation was ‘contrary to the letter, to the spirit, and to the policy of the Act of Parliament’. Eardley subsequently reported that Hawkins ‘quietly let the matter drop’. Unfortunately, Parliament could do little with regards to the University, as each statute, in isolation, was within at least the letter of the law.

Sir Culling Eardley Eardley, third baronet (1805–1863) by George Sanders, published 1865 (after W. Roeting), Ashmolean Museum, Oxford.

Given the overall resistance to reform from the University authorities, it is unsurprising that the government efforts of the 1850s did not effect all changes desired by the wider community to bring the University in line with the more progressive ideals of the age. The authorities’ attempts to evade the ‘spirit’ of the law simply meant that further reform, commissions, and legislation quickly came onto the horizon.

Faye McLeod, Keeper of the University Archives.

More from the Blog

Follow us on Twitter here.